Despite So-called “Withdrawal”, US Has Far from Given Up Its Designs on Iraq

Iraq and the institutions built there since the 2003 invasion remain of central importance to the US and wider Western ambitions for the region.

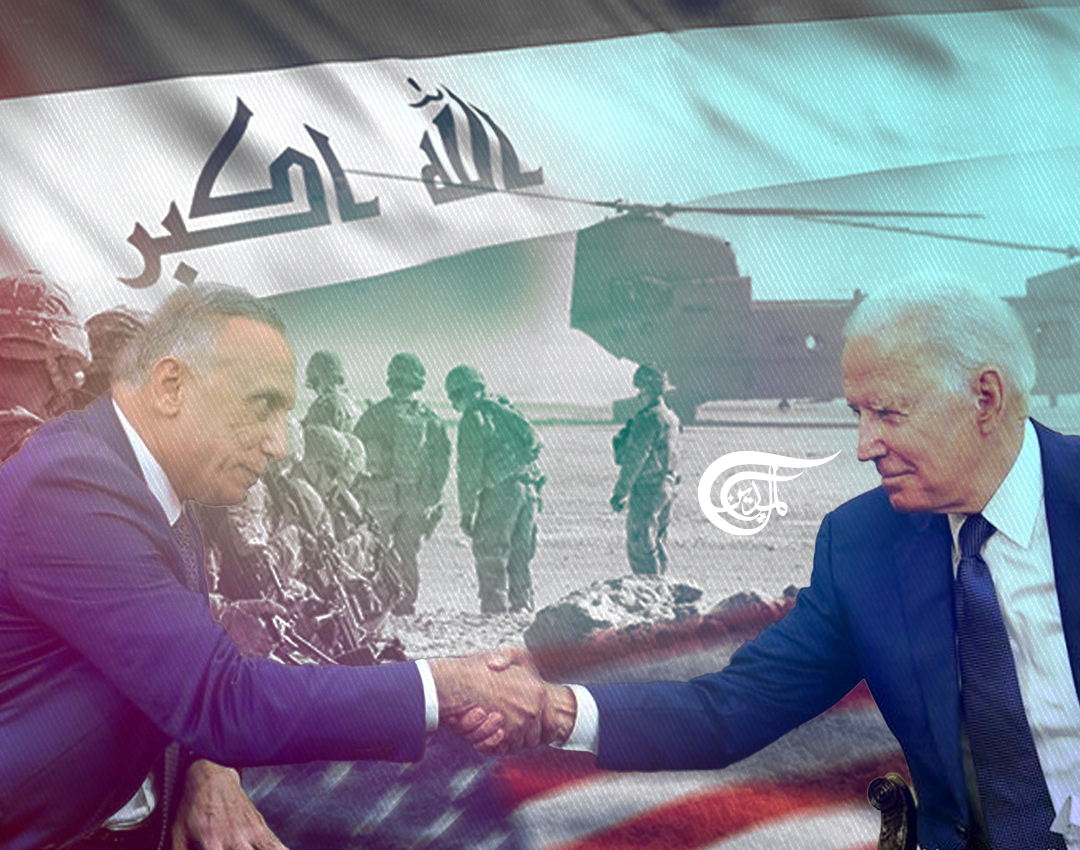

Iraqi Prime Minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi’s state visit to the White House last week was a textbook case of face-saving obfuscation, for himself as well as for US president Joe Biden. For the US president, it represented the symbolic but illusory transformation of his country’s military footprint in Iraq into an “advisory role”. For Mr. Kadhimi, it was not only meant to placate the many voices within Iraq calling for complete US withdrawal, but an attempt to present the future US-Iraq relationship as being one of equals, between two totally sovereign states.

Were that in fact the case, then president Biden, a dyed-in-the-wool foreign interventionist would not have acceded so meekly.

Iraq and the institutions built there since the 2003 invasion remain of central importance to the US and wider Western ambitions for the region. The American hesitancy in initially withdrawing at the start of the 2010s was due in large part to the fact it had created a power vacuum in the heart of the region.

Without Saddam Hussein and his largely Western-armed military machine hemming in the Iranians, complete US withdrawal would have seen Tehran fill the void, solidifying its arc of influence stretching to the Syrian and Lebanese coasts.

Needless to say, this ‘new’ US-Iraqi strategic dialogue will involve continuing support to the post-invasion political and military elite, which Washington has tasked with subduing the Popular Mobilization Forces and blocking Iranian aid and material to its allies in Syria and Lebanon. The expected demand of the conventional armed forces for weapons and material no doubt has defence companies on both sides of the Atlantic salivating.

Amid the usual diplomatic niceties, the most telling sentence from the two leaders’ joint-statement declared that, “the United States expressed its support for Iraq’s effort to promote economic reform and enhance regional integration, particularly through energy projects with Jordan and the GCC Interconnection Authority.”

It is by now well publicised that Washington is pushing Iraq to merge its electricity grid with that of the GCC and other regional Arab states so as to break its energy dependence on Iran.

US attempts to cement Iraq among its array of Arab allies dovetail with the accelerating pace of normalization with “Israel”, particularly by the GCC member-states. With multiple far-reaching initiatives converging on the southern Levant and northern Red Sea, this integration designed to permanently tie the fortunes of the Arab states to the fate of “Israel”.

The ‘Tracks for Peace Initiative,’ already underway, seeks to link the rail-networks of “Israel”, Jordan and the GCC states, creating a commercial land-bridge between the Persian Gulf and the Mediterranean, bypassing the straits of Hormuz and Bab al-Mandab. The envisioned volumes moving along this corridor are projected to reach US$250 billion annually by 2030.

Meanwhile a supposedly separate but unmistakably familiar project has gathered pace throughout the first half of the year, known as the “New Levant Economic Initiative”, a tripartite security and economic alliance between Iraq, Jordan and Egypt. The project is openly touted as a means of isolating Iran and shoring up Western economic interests in the region, the greatest of which lie in the astronomical sums still to be spent on Iraq’s post-war reconstruction and future recycling of its energy surpluses. Among the components of the entente is the 2000km Basra-Aqaba oil pipeline, which will also circumvent the maritime chokepoints and could be extended to the Mediterranean via Egypt, or conceivably also “Israel”.

Like Egypt and the GCC states, Iraq is set to embark on a construction frenzy, with at least 12 entirely new residential cities, a new capital outside of Baghdad, energy-megaprojects and what it hopes will become the region’s leading shipping hub, the Grand Faw Port near Basra. With more than US$100 billion worth of construction projects already lined up, the US and other Western governments have long eyed the Iraqi economy as one of the future drivers of global economic growth.

With all the other players in this trend either in the process of normalizing or already having direct relations with “Israel”, it is difficult to see how Iraq’s inclusion would be intended to lead to anything other than normalization with the Israeli state and full integration into the US-led regional military architecture.

Syria, which has similarly been devastated by years of foreign armed intervention, presents yet another tempting economic prize, with its own reconstruction also likely to require several hundred billion dollars of investment. Were it to be cornered in such a way, this ‘New Levant’s’ architects may well seek to lure it into economic liberalisation, while severing, in exchange, its ties to the ‘Axis of Resistance.’

With so much political (and actual) capital converging on the Eastern Mediterranean and Northern Red Seas, it seems fanciful to assume the US sees its role in Iraq as over, or that it won’t “advise” the country in the direction of ever greater economic liberalisation and normalisation with the Israeli state.

Samuel Geddes

Samuel Geddes

5 Min Read

5 Min Read