Bahraini Prisoners: 'We Have A Right' vs. The Slow Killing Policy

The “We Have a Right” movement is the expression of prisoners of conscience that the suffocating restrictions - depriving them of their rights and ignoring their repeated demands - have reached an unbearable peak.

-

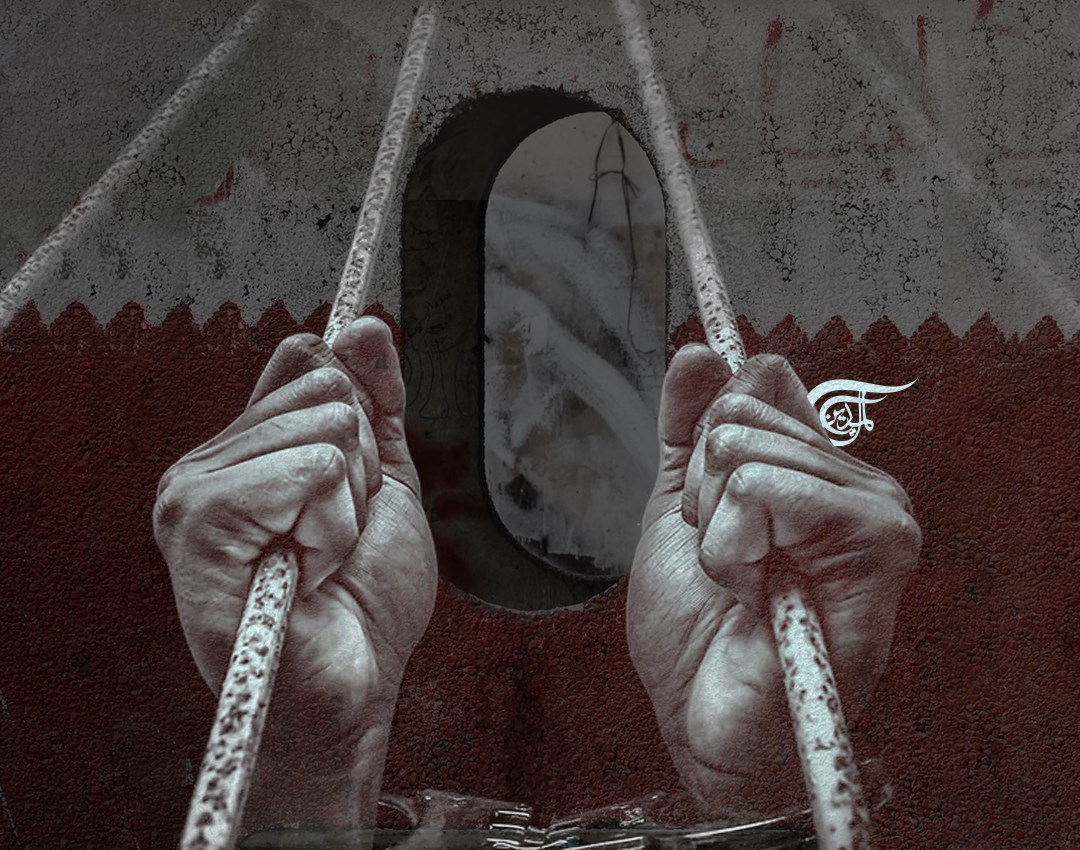

The ordeal of Bahraini political prisoners (Illustrated by: Zeinab ElHajj, Al Mayadeen English)

After more than twenty days of hunger strike, the number of prisoners of conscience on hunger strike has reached 761 after the strike began with 460 strikers on August 7.

They are Bahraini citizens who are not supposed to be detained in the first place, let alone being arbitrarily detained and also deprived of their basic prisoners’ rights.

In the statement they issued when they launched their protest movement "We Have a Right", the prisoners of conscience expressed the daily suffering they face, from arbitrary isolation of some prisoners to deprivation of many of their rights, including the freedom to practice religious rites, and the psychological and physical humiliation they are subjected to on a daily basis. In addition, all prisoners, in general, are kept twenty-three hours a day inside their cells, while they are allowed to go out for only one hour a day in order to fulfill almost all their needs, including making phone calls with their families, hanging washed clothes, doing sports, and getting exposure to the sun. In their statement, the protesting prisoners complained about "the unjust visitation system with its glass barrier and the reduced time and number of visits... Let us not forget our wasted right to education, with a hateful political intention to make us ignorant, as well as our right to health care, as it is no secret to anyone that the health situation is in crisis."

This is not the first time that detainees have chosen to go on a hunger strike in Bahrain's prisons. Rather, throughout every year since the beginning of the political crisis in February 2011, independent human rights organizations monitor many individual cases of hunger strikes and other forms of protests. During this year, 2023, 51 cases of hunger strike took place individually, the last of which was during the ongoing month of August, when six child detainees went on hunger strike in Dry Dock Prison to protest the failure to implement the Juvenile Justice Law for their cases. Before that, the detainee, Muhammad Hassan Al-Raml, went on hunger strike four times at close intervals because he was (and still) deliberately deprived of proper medical treatment, and after being promised every time that his demands would be taken into consideration by the prison administration, he would end his strike, only to go back to it after discovering that the promises were false as they have never been fulfilled.

This vicious circle is constantly repeated in Bahraini prisons. It begins with a case of ill-treatment or denial of medical treatment, followed by demands from the deprived or ill-treated prisoner to obtain his rights. His demands are not met, so he resorts to a hunger strike, and he receives promises that his demands will be taken into consideration in return for suspending his strike. He suspends his strike, but the promises would not be fulfilled, so he engages in a hunger strike again, and so on and so forth in the best-case scenario. However, in some cases the strike is not met with promises, but rather with threats and further denial of the right to phone calls and isolation in solitary confinement.

This time, the matter is different. The “We Have a Right” movement is the expression of prisoners of conscience that the suffocating restrictions - depriving them of their rights and ignoring their repeated demands - have reached an unbearable peak.

Hunger strike is not an easy option. Rather, it is the last means prisoners resort to after they have exhausted all means of claims and pressure to obtain their rights because going on hunger strike entails severe suffering for the strikers, and the longer it lasts, the more painful and dangerous it is for them. All these measures are taken for the purpose of putting pressure on the oppressive ruling party. Prisoners do not resort to sacrificing their lives unless their demands are crucial. This is exactly what the prisoners of conscience on hunger strike expressed through leaked audio messages, as many of them used the term "slow killing" to describe the restrictions they are subjected to on their rights inside prison.

One of the protesting prisoners of conscience, Hussein Al-Mahari, said the prison administration opts for a policy of collective punishment and slow killing, and this has led to the death of a number of prisoners. Another protesting prisoner, Muhammad Al-Baqqali, said, "We are going on an open strike in order to stop systematic injustice" and that "the denial of medical treatment and slow killing are subjected on all categories of prisoners, including political figures, leaders, and youth." Prisoner of conscience Muhammad Farsouni said, "We are subjected to the worst methods of psychological and physical torture, medical neglect, and slow killing."

More than 50 audios were leaked by detainees from inside Jaw Central Prison, in which they stated their demands and expressed their suffering, based on previous experiences. They stressed that such acts (leaking protest audios) have dire consequences inside the prison. Detainees held in solitary confinement recorded their audio demands, and yet, prisoners of conscience continue to leak messages from the beginning of the strike until today.

Those who choose to go on hunger strike, protesting the slow killing policy, are always expecting solitary confinement or other forms of torture and ill-treatment because of their leaking audio messages. In his audio message, Mahmoud Atiyya said, "Either we receive the fulfillment of our demands if we keep silent or we face martyrdom." Sadiq Al-Alwani, another prisoner of conscience, said, "The strike is launched in order to save our lives from danger, for it seems continuous that some prisoners are released from prison as martyrs, while the rest of the prisoners are in solitary confinement and targeted to be killed morally and healthily."

Today, after 18 days of the hunger strike, the health of some of the striking detainees has deteriorated, as the level of sugar in the blood of many of them has become low and many of them fainted, with some even transferred to hospital.

A main question arises: What if the worst happens? What if one of the hunger strikers dies? Would this have an impact on the behavior of the Bahraini authorities toward the detainees and their demands? Previously, 14 detainees were released dead from prison due to deliberate denial of medical treatment or due to torture between March 2011 and June 2021. Moreover, 8 former detainees died due to complications from the torture and denial of medical care; they were released in very deteriorating health conditions. Those cases happened between June 2011 and the last one was of the former prisoner of conscience, Muhammad Abdullah Yaqoub Al-Aali, who died less than two months ago on July 5, 2023, from lung cancer. Symptoms of his illness had started in 2016, and he submitted his complaints to the prison administration and governmental human rights organizations, but the prison administration ignored his demands until his condition began to deteriorate significantly in 2020, and still, the necessary treatment was not provided for him. When his condition deteriorated severely in 2021 due to his infection with COVID-19, which exacerbated his lung cancer, the authorities released him while he was in a very poor health condition after 5 years of intentional medical negligence and complete disregard for his submitted demands.

The victim Mohammed Abdullah Al-Aali and 21 prisoners of conscience are examples of the result of the slow killing perpetrated by the Bahraini authorities in prisons. These cases did not affect the behavior of the Bahraini authorities and did not prompt them to improve prison conditions and treatment methods for detainees. Moreover, the international human rights community did not take pressuring measures against the Bahraini authorities over those fatality cases. Furthermore, the Bahraini authorities were not deterred from continuing the same retaliatory measures they use against anyone who openly opposes their public policies or practices.

So back to the question, what if the worst happened to the hunger strikers? The answer is that the worst has happened in the past more than twenty times, and the Bahraini authorities have not yet been deterred. What the prisoners of conscience in Bahrain currently need is interaction from outside Bahrain alongside the broad popular interaction taking place inside Bahrain. The popular interaction within Bahrain is natural because what’s happening in prisons is the people’s cause, and they must take the lead in it. However, sincere interactions of people, international organizations, and bodies from outside Bahrain would affect the positions of foreign governments toward Bahrain and thus exert pressure on the government of Bahrain and affect its reputation. Unfortunately, domestic human rights organizations work day and night to praise the Bahraini government and try to present it to the world as a government that respects human rights and cares for the rights of its citizens.

However, the real criterion for its image is what the hunger-striking prisoner Hussein Al-Zaki expressed through his leaked audio, "Whoever wants to know the truth about the Bahraini authorities must take a look at the prisons." This is what the world must know, recognize, and deal with the Bahraini government on a realistic basis.

Ghina Rebai

Ghina Rebai

9 Min Read

9 Min Read