When Europeans became Semites

Researchers, historians, and theologians have debated the origins of European Jewry for centuries. Except for the roughly 100 Jewish captives who were brought to Rome as slaves in the period 66-73, European literature offers little information linking European Jews to Palestine, nor a significant collective presence or widespread persecution of Jews prior to the 11th century.

-

Israeli historian Shlomo Sand discussed the origin of European Jewry in great detail in his 2008 book, The Invention of the Jewish People.

Inarguably, anti-Jewish racism was intrinsically a Western phenomenon, whereas other cultures did not experience it quite the same way. Western anti-Jewish racism could be attributed to religion, rejection of Christ, and crucifixion, evolving throughout history into various forms of hatred toward Jews in particular, as well as against non-Christians in general.

The four European Crusades were one episode targeting Muslims in Palestine, in which atrocities were committed against Palestinian Christians and Jews alike. Ostensibly, the Crusades’ earthy slaughter of Muslims, Arab Christians, and Jews, was predicated on a benevolent belief to save them from god’s hell. Nevertheless, as a group living under European dominion, Jews have suffered the worst cruelty, culminating in the Holocaust.

The conspicuous escalation of hatred against Jews between the 11th and 13th centuries could be construed as an indirect measure of the expanding Jewish community in Europe. As such, this raises the question regarding the perceptible growth of the Jewish population, particularly, after the 11th century, and its plausible connection to the rise and demise of the Khazar Empire.

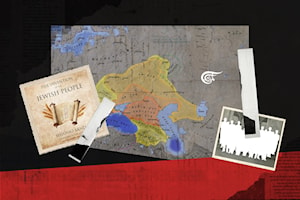

In the late 8th century, King Bulan of Khazaria led a mass conversion from paganism to Judaism. Bulan’s Kingdom became the first institutionalized collective Jewish entity in the history of Eastern Europe. The prosperous and powerful Jewish Kingdom was the largest, and longest lasting unified Jewish sovereignty in history. It ruled for several centuries the Caucasus region, encompassing southern Russia, Crimea, and large swaths of today’s Ukraine including Kiev.

In the 11th century, the Jewish Empire experienced its first defeat in a joint Russian and Byzantine invasion. The 1016 war represented an inflection point in the empire’s gradual demise, and the outset of a westward Khazari migration. In parallel, it showcases the clear correlation between the decline of the Jewish Reigns, and the incremental emergence of the Jewish population in Europe.

The empire lingered in a slow death for 200 more years over ever-shrinking territories until it crumbled under the Mongols in 1224. The Mongol invasion left Khazaria devastated and its subjects in a wholesale flight. Hence, the birth of the only documented “Jewish diaspora” throughout the European continent.

Israeli historian Shlomo Sand discussed the origin of European Jewry in great detail in his 2008 book, The Invention of the Jewish People. Initially, Sand’s primary interest was to write on the presumed forcible Jewish exile from historical Palestine. He was, however, astonished to establish in his earlier exploratory research that the expulsion story couldn’t be corroborated with historical evidence. Then, his investigation took him into an unexpected course, where he concluded that Central and Eastern European Jewish ancestry stems from the 8th-century mass conversion in Khazaria, not Middle Eastern Jews.

Another study was published about the same period by Israeli geneticist Eran Elhaik at John Hopkins University. According to the genetic empirical evidence, which was published by the Oxford University Press in December 2012, the Israeli scientist discovered that European Jews share a common genome structure that gravitates to old Khazaria, not the Middle East.

“The majority of (European) Jews do not have a Middle Eastern genetic component,” Dr. Elhaik told Israeli newspaper Haaretz in 2012.

Then, what happened to the Jews of the Arab World?

Insofar as the Roman expulsion hypothesis, we must keep in mind that the contrived exile fable was propagated by early Christians as “divine punishment” on Jews for rejecting Christ. Though religious Jews rejected this notion, political Zionism in the late 19th century tolerated the "divine punishment" tales as an agency for linking (exiled) European Jews to Palestine.

The more plausible theory supported by Sand’s book, Jews remained in the region and experienced assimilations, including conceivable religious conversions, first to Christianity and later Islam. Jews were no exception to other people in the area who integrated into the new burgeoning Arabic and Islamic culture in the early part of the seventh century.

An example, one can find today a common last name among Palestinians like Sahiun, an Arabic modifier for the noun Zion. It’s likely that such names point to the original Jewish root of those families.

Nevertheless, like Arab Christians, some Jews continued to maintain their beliefs and built affluent Jewish communities in places like Baghdad, Damascus, Cairo, and Beirut, as well as in other Arab cities.

In Beirut, I am personally familiar with the Jewish neighborhood of Wadi Abu Jamil where Jews continued to live in peace with their Christian and Muslim neighbors following the creation of "Israel". The neighborhood was protected by Palestine Liberation Organization fighters during the Lebanese Civil War in the mid-1970s. Sadly though, almost all left, possibly due to Israeli intimidation, inducement or both, following the 1982 Israeli military occupation and withdrawal from the Lebanese capital.

Genetics, history, anthropology, and archeology, have inconvertibly proven that Muslim and Christian Palestinians have more genetic similarities to the original Jews―who migrated from Mesopotamia to Palestine some 3500 years ago―than European Jews.

Like the “divine creation” theory attempts to validate creationism, the “divine punishment” of (expelled) Jews to explain history, failed the test of time and science. This is not just a mere opinion, but also represents the findings of two Israeli scientists: one is an expert in genetics, and the other a professor of history.

Jamal Kanj

Jamal Kanj

5 Min Read

5 Min Read