Mind the (Language) Gap

English reading and writing, the supposed language of Empire and global lingua franca, became a bridge between peoples and an instrument of resistance.

Al Mayadeen has decided to launch an English version, taking a step forward to include new trends within the Global South. We, as Venezuelans, can easily belong to and understand what such a decision bares, highlighting the necessity to take this indispensable initiative.

There can be simple reasons and outright options like expanding and reaching a wider audience. On this level we could think about “obvious” and pragmatic reasons that perhaps are reachable, such as the benefits of getting into different linguistic geographies, different cultural circuits, testing the grounds of other ratings, and setting metrics that could be understood as the rationales for market strategies. And sure, it is hard to reject such valid reasons. But only relying on that approach can lose sight of the deeper possible meanings.

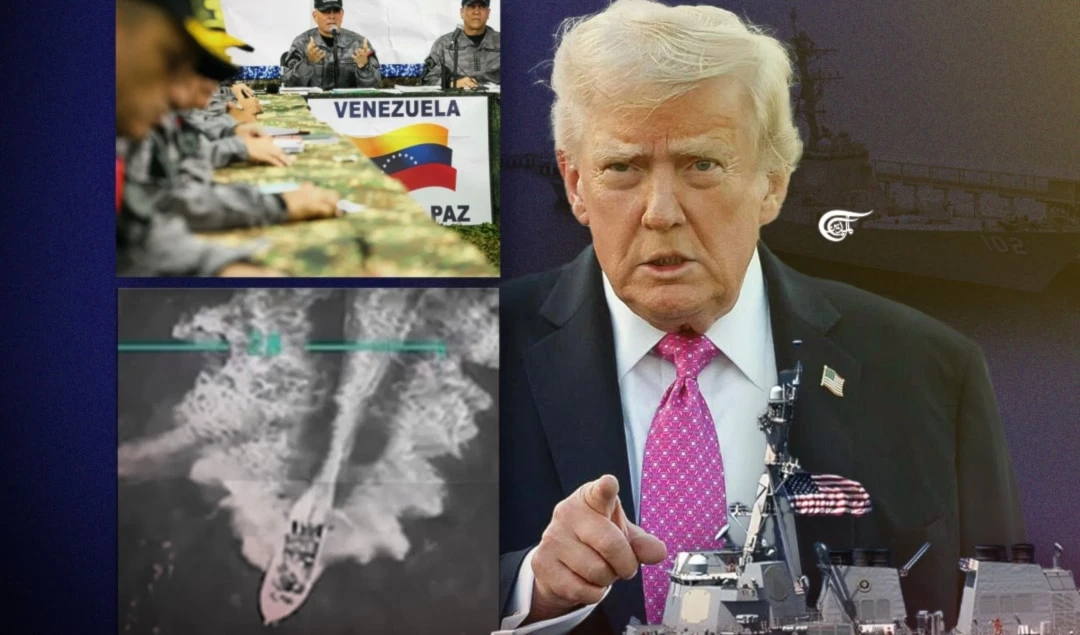

There's one approach at plain sight that needs to be stressed, regardless of how explicit it could possibly be. Countries and whole regions that have been subject to intense, multi layered, aggressive foreign meddling, and nations that face economic, military, diplomatic, and socio-political disruption – Hybrid Warfare, can be subsumed under the current conceptual jargon– know that the so-called narrative is the first –and perhaps– the final step. Words that set the story are the basis for every sort of justification, be them legal, diplomatic, institutional, military or plain social perception of several audiences –local on targeted nations, domestic inside the countries engaging in these sorts of operations.

A clear, descriptive case in point, of course, is Western Asia. In 2003, Iraq could have set the groundwork on other countries; a framework that was established less than a decade after. Libya could be the more extreme example of how this succeeds, Syria perhaps the opposite. A perceived “reality” had to be created in order to advance, notwithstanding widespread opposition to these methods and regardless of political stances inside the targeted countries. A narrative was imposed, humanitarian justifications made. But it was all about the final outcome –regime change, regional political/social engineering, geopolitical realignment, traumatic transfer of sovereignty in order to discipline the local population and meet the strategic interests of desperate Transatlantic economic needs.

A tandem narrative set between on-the-ground “reality making” confirming a story fit for Western-controlled sensitivities and well-developed metaphysics finally “confirmed” by any or every multilateral body with leverage able to sugarcoat mere brutality. Specific contexts never mattered, shaped (Western) feelings did. Victims annulled. And, above all, control of the alleged story, widespread among different audiences in order to build a staged/managed perception. Easily summarized now, this mechanical template has been thoroughly exposed during the last decade by many outstanding people.

Needless to say, the real substance of these technicalities are the lives of innumerable people and every particular universe they bared or keep baring. Narratives also kill. In this last sentence and the previous paragraph, I strongly rely on Sharmine Narwani's work, among a wider and important list of people that have faced and decoded this process.

This brings me to my next point. Around seven years ago, the country where I live started to go through a similar process, based on the same methodological regime-change framework, or at least its main component became more visible. We started reading the work of Sharmine and others, based on their own knowledge and experience. She and others were writing in English, and some of us were able to compare their notes with ours, bringing them into our own context and trying to set similarities between the readings and our own experiences. This triggered an indirect, rich and insightful exchange process that gave us the tools to cope with and manage our own situation on every possible level.

English reading and writing, the supposed language of Empire and global lingua franca, became a bridge between peoples and an instrument of resistance. Interesting times.

In 2019, with the Juan Guaidó misadventure in full swing, all these tools –and English properly– became a decisive strategic aspect of how to face this new and almost unexpected situation. With the help of English-speaking Western journalists and activists, along with English-speaking people across the Global South, we started to bring the fight on global terms, overcoming our accustomed Spanish insularity and preventing the info siege from stifling us. This was a silent battle along the rest of them. And I think that it can bring home the point I wanted to prove.

So, in a way, in several places, we've been also starting to conquer the right to tell our story in their language, not only ours. But this brings to the table a final argument. Perhaps we can't be that knowledgeable of how people live inside transatlantic societies, but we definitely know and understand better how they work outside their borders. And we also know they also suffer domestically, and to reach them would be an act of solidarity and compassion. We're also fighting against their own isolation from the world. Translation, thus, is also an act of solidarity.

The “in-the-middle” –as George Steiner could suggest– movement within expressing ourselves, the bridge decoding our experiences, makes contact with the deepest elements of our human spirit, and this quadrant doesn't need words to be understood.

As Dr. Bouthaina Shaaban, advisor to Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad, recently told me that narrative is also a battlefield. And in the same way, it can be turned into the main vehicle for peace.

Diego Sequera

Diego Sequera

5 Min Read

5 Min Read