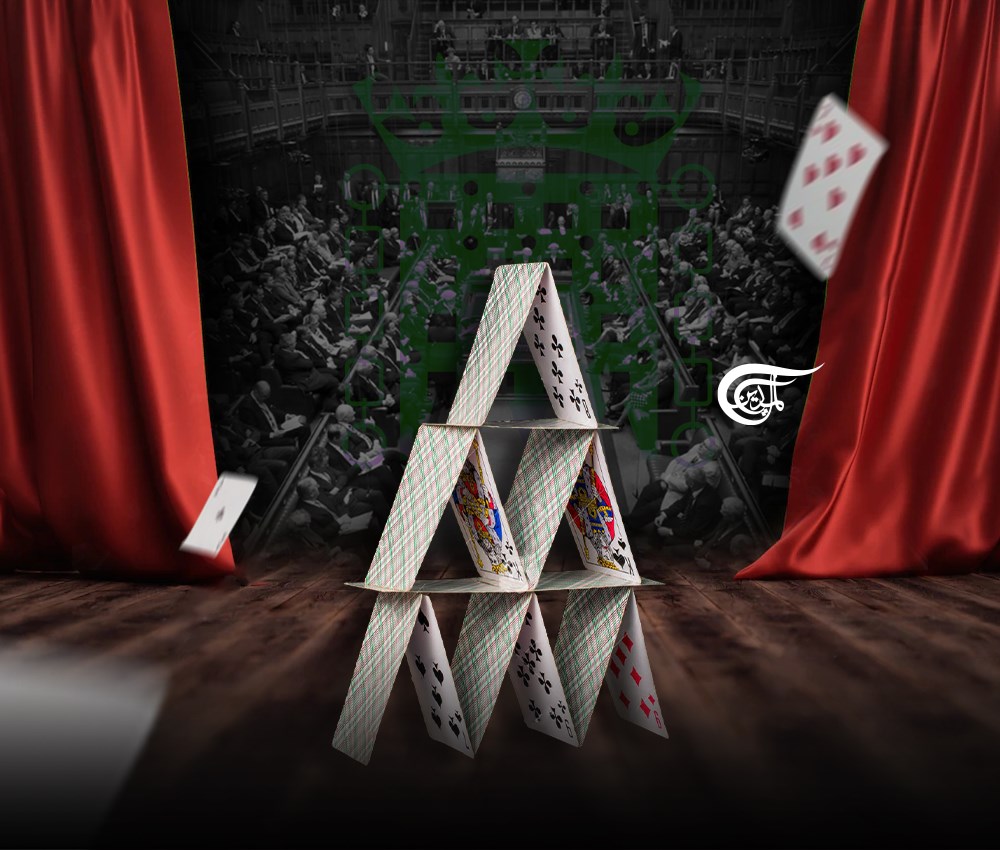

News from Nowhere: Crooked House

It's increasingly obvious that, in order to regenerate an ailing nation, the structures and practices of UK politics must themselves undergo a major upheaval.

When, in the dying days of Liz Truss’ brief premiership, reports emerged of MPs being bullied and jostled in the voting lobbies of the UK parliament – in a situation of what the government’s own Chief Whip later described as ‘chaos’ – one broadcast commentator unkindly suggested that the House of Commons had descended into the kind of anarchy more often expected of Italian politics.

This comparison seemed not only unfair but also oddly unaware. Being so accustomed to the unedifying spectacles enacted on a daily basis in the Palace of Westminster, we British tend to forget how ridiculous the conduct of our parliamentarians must appear to external observers. They’re not allowed to applaud, yet they can cheer, jeer, heckle, and groan. Backbench Tories in their committee meetings even signify approval by banging on their desks like a gaggle of unruly schoolboys.

It's raucous and undignified, more like a drunken evening at the debating society of one of the older universities than a model of modern democracy. This is in part the result of the fact that so many senior politicians (especially on the Conservative benches) cut their political teeth in those same undergraduate debating clubs. It may also be the consequence of the eight bars which serve subsidized drinks to MPs in the Palace of Westminster itself.

It is, in short, the legacy of centuries of domination by privately educated, overprivileged Englishmen. The pomp and ceremony of its ancient traditions present a literal embarrassment of riches.

If this is political theatre, then it's a drama staged by one of the medium's more radically anarchic directors. It’s the theatre of the absurd. It makes Edward Bond’s Lear look like Michael Bond’s Paddington. It makes Ubu Roi seem restrained.

Across the world, many contemporary parliament buildings are laid out in the round, but the UK's Commons chamber sets the government benches directly facing the opposition parties on the other side of the House. Rather than promoting consensus, this architecture emphasizes the confrontational character of politics, underpinning the stereotypical and artificial opposition between left and right.

Overall, the Palace of Westminster is in a terrible physical state, a site of dodgy plumbing, unreliable wiring, and crumbling masonry. Its antiquated physical edifice reflects and reinforces its outmoded ethos.

There have been plans for several years to move the UK’s parliamentarians to a modern conference center nearby for an extended period, which would be required to allow for the full refurbishment of the Westminster estate. Estimates of the costs of this exercise have however repeatedly proven to be prohibitive. It has even been suggested that they might be relocated to more suitable and affordable facilities outside of London, as part of plans to sponsor the economic regeneration of poorer regions of the country.

If the United Kingdom is to revive its political fortunes and promote policymaking based on rational dialogue between diverse perspectives, if it is to restore its reputation on the world stage and reinvigorate trust in democratic processes among its own people, then such a move cannot come too soon.

A recent poll showed that less than twenty percent of young British adults have faith in the institutions of democracy. As we continue to witness the re-emergence of would-be demagogues across many western nations, this should be viewed with significant anxiety. A radical change in the conduct of our politics is clearly urgently needed.

Yet Westminster today feels like a hangover of Dickensian Victoriana, a realm in which Mr. Bumble the beadle might raise his grand golden staff of office to call Mr. Fezziwig's followers to order.

Politics is often compared to reality television or to a soap opera, but the UK parliament lacks that contemporary appeal. It boasts the culture of a gladiatorial arena in the style of a nineteenth-century gentlemen’s club, Oscar Wilde and Mycroft Holmes exchanging barbed aphorisms, as they lounge upon plush leather banquettes in the heart of Pall Mall. This is cage-fighting at the Athenaeum. This is Hogwarts meets Fight Club.

In September 2019, an image of the Tory Leader of the House of Commons reclining on the front bench during a key parliamentary debate went viral, and for many demonstrated just how out of touch with the realities of ordinary life Westminster had become. The MP in question was none other than that lazy libertarian, the Right Honourable Jacob Rees-Mogg, son of the late Lord Rees-Mogg, erstwhile editor of The Times newspaper.

Young Jacob was the product, like his close ally Boris Johnson, of the elitist education offered by Eton College. He quickly grew into a curious cross between Lord Snooty and a six-foot-tall praying mantis. A social conservative, a cheerleader for laissez-faire capitalism, and a zealous Brexiteer, he runs a multi-million-pound investment fund that has profited remarkably well from Britain’s departure from the European Union.

He attempted to defend his display of contempt for parliament by arguing that he had been ‘restoring an ancient tradition’ by which senior government ministers would put their feet up on the table in front of them, the Table of the House on which rests its ancient symbol of royal authority and parliamentary legitimacy, the silver-gilt ceremonial mace.

This single act, exacerbated by its appallingly insensitive defense, captured all the reasons behind the public disdain for the antediluvian arrogance, hauteur, and disconnection so often displayed in the culture and conduct of MPs, that common perception of their lordly sense of entitlement.

Meanwhile, a parliamentary committee continues to investigate whether Boris Johnson, while Prime Minister, lied to MPs about attending parties in Downing Street during lockdown. If it finds that he did, public concerns as to the integrity of their elected representatives will again be confirmed. But, if it exonerates him, public outrage will focus on the House itself.

And that’s just the House of Commons. The degrees of shock and sheer disbelief provoked by the conduct of that institution seem very minor when compared to how any reasonable person might react to the arcane customs – and indeed the very existence of – Westminster’s upper chamber, the House of Lords, the sleepy domain of political appointees, bishops, and the ghosts of hereditary peers.

Maybe Guy Fawkes was right after all – though the impact of thirty-six barrels of gunpowder might these days be considered somewhat excessive. A couple of firecrackers, a blast of Stormzy, and a copy of the Morning Star should be enough to see off the lot of them. Some might even up the dosage of their somniferous medications to levels that err on the side of incaution.

But let’s not even get started on that. A referendum on constitutional reform, although possibly just as soporific, would certainly also do the trick.

Last month, the British Labour Party announced that, if voted into government, it would seek to replace the House of Lords with an elected second chamber. This has become necessary because, as Labour leader Keir Starmer said, the people of the UK have ‘lost faith in the ability of politicians and politics to bring about change’.

Also last month, the parliamentary expenses watchdog advised that MPs could claim the cost of Christmas parties as legitimate expenses. This guidance was roundly rejected by politicians of all ideological hues as being extraordinarily out of touch with the mood of the public during a cost-of-living crisis that has wreaked devastating effects on the lives of ordinary working people and their families across the country.

Indeed, according to that watchdog’s chief executive, MPs had received ‘abuse’ as a result of media reports that they would be allowed to use public money to fund their seasonal festivities in this way.

The parliamentary theatre of the absurd is descending into farce. A fortnight ago, the BBC’s flagship morning news programme accidentally replayed the previous day’s edition of its daily ‘yesterday in parliament’ feature. As one of the show’s presenters supposed, there should have been a prize for anyone who’d noticed.

That week, four Conservative MPs announced their decision not to stand for parliament at the next election. The press has since reported party concerns as to the threat of an exodus of their parliamentarians.

Then, last week, it was reported that one Tory Member had decided to fight against a recommendation by the Commons Standards Committee that he be suspended for breaching the MP’s code of conduct for inappropriate corporate lobbying ‘on multiple occasions and in multiple ways’.

At the same time, another Conservative politician completed a three-week stint on a reality TV show, while he was supposed to have been representing his constituents in the House.

Just a few days ago, the Commons Public Administration Committee criticized the reappointment of the Home Secretary less than a week after she’d had to resign for breaching the ministerial code.

Many British people’s understandable indifference to, or detachment from, their parliament is a real and present threat to the continuing integrity of the United Kingdom. Two weeks ago, the country’s Supreme Court published its response to the Scottish government’s demand for a referendum on independence, which had previously been blocked by Downing Street. Although the court backed the British government’s decision, the case again highlighted a growing sense of public alienation from the world of Westminster.

It's increasingly obvious that, in order to regenerate an ailing nation, the structures and practices of UK politics must themselves undergo a major upheaval. It’s time to tear down this house of cards and build in its place something rather more sustainable and sustaining for a society and state approaching the hefty challenges of the second quarter of the twenty-first century.

Today, the Labour Party published a report on the political future of Britain, authored by former Prime Minister Gordon Brown. It described the existence of the House of Lords as 'indefensible', proposed the devolution of powers and resources to local regions, and promised 'the biggest ever transfer of power from Westminster to the British people'. With so much now at stake, such radical ideas as these may represent the last best hope for the continuing democratic and constitutional integrity of the UK.

Alex Roberts

Alex Roberts

10 Min Read

10 Min Read