News from Nowhere: State of Decay

This column usually attempts to find the lighter side of the ongoing series of calamities that have recently come to characterise British political, economic, and social life. But there’s really nothing funny in any of this. I’m sorry, but I’m afraid there’s nothing much to laugh about here.

-

The British public may not have been reassured when the chief strategy officer for the NHS in England told the BBC that "you can’t call it a crisis if there isn’t a plan, and we’ve got a clear plan."

British newspaper front pages last month were filled with reports of the death of a two-year-old child as a result of prolonged exposure to untreated mould in the social housing home his family occupied. No remedial action had been taken despite repeated concerns raised by his parents. This tragic case exposed more widespread problems across the UK housing sector.

There was, of course, general outrage that children’s lives should be put at risk in this way in the world’s sixth-largest economy.

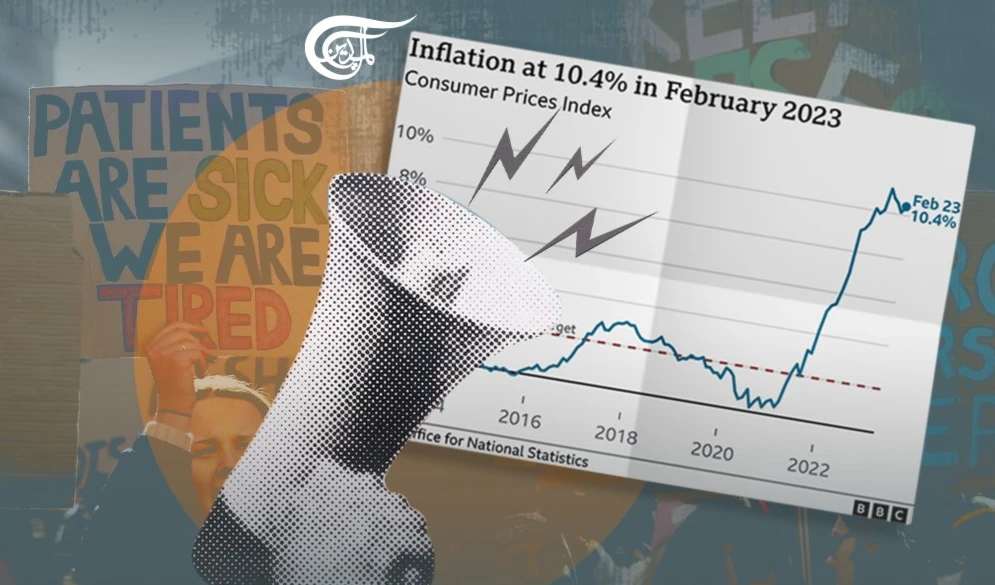

Meanwhile, rampant rates of inflation have made it increasingly difficult for ordinary British people to feed their families, heat their homes and drive to work. Last week’s sudden spell of arctic cold weather certainly hasn’t helped.

A report published earlier this month suggested that the UK’s departure from the European Union had added six per cent to food costs. In the run-up to the festive season, analysis conducted by the BBC suggested that 2022’s Christmas dinners would be 22 per cent pricier than last year.

Figures also released this month showed a 15 per cent drop in Britain’s number of exporters, even as it was reported that the government had fallen significantly short of its target for establishing international trade deals after Brexit. Nevertheless, government suggestions that Britain might re-join EU single market mechanisms were quickly slapped down by backbench Tories.

Of course, the war in Europe and the market meltdown provoked by the rash fiscal policies of Liz Truss’s brief premiership have only served to make the country’s economic situation even more dire. In particular, the self-fulfilling idiocy of Liz Truss’s uncosted tax cuts and planned hikes to national debt pushed interest rates up, and that shift in itself significantly increased those levels of debt. Truss’s childlike optimism, apparently unhinged from all economic realities, made the ebullient Boris Johnson, up till then renowned as the Wilkins Micawber of modern British politics, look like the dourest prophet of doom.

As the shadows of stagflation gathered last week, the new Chancellor warned that things would have to "get worse before they get better."

At the same time, train cancellations have hit a new peak, with one in twenty-six scheduled journeys pulled. Schools, unable to meet rising costs, are laying off teaching staff, and hospital waiting lists have hit record levels.

Earlier this month, it was reported that ten thousand ambulances each week are caught in queues of at least an hour outside accident-and-emergency units in England, and that in one case an eighty-five-year-old woman with a broken hip had waited forty hours before being admitted to hospital. Forty per cent of people admitted to emergency departments are waiting for at least four hours for a hospital bed. The numbers waiting more than twelve hours on a trolley have this year exceeded the total for the last decade combined.

The great British public may not have been entirely reassured when this month the chief strategy officer for the National Health Service in England told the BBC that "you can’t call it a crisis if there isn’t a plan, and we’ve got a clear plan."

Last month saw the continuation of strikes by rail workers and mail workers, and the announcement of plans for the first national nurses’ strike in the country’s history. Paramedics have also announced their intention to go on strike, as have staff at the Department for Work and Pensions, the Highways Agency, and UK Border Force.

Earlier this month, the Chairman of the Conservative Party announced government plans to deploy military personnel to drive ambulances, fight fires and secure the nation’s borders if all the threatened plans for industrial strike go ahead. (But, while they may manage to handle baggage at airports, it remains unclear whether members of the armed forces will be able to replace striking driving test examiners without knocking the fear of God into anxious learner drivers.) He added, rather petulantly, that it was "unfair" of key unions to schedule strikes at this time of year, as they would spoil everybody’s Christmas.

This new winter of discontent has now come to represent what the BBC’s business editor last week described as the worst "collision between workers and employers" he has ever seen. The government has ignored requests by unions to participate directly in negotiations and is even threatening to legislate against key workers’ rights to withdraw their labour.

Even universities were hit last month by a lecturers’ strike, and Scottish schools closed when teachers went on strike. Teaching unions in England have been exploring the possibility of similar action.

Scotland was also shocked by leaked reports that its hospitals were considering the early discharge of patients as a prospective measure to address that nation’s healthcare crisis. This crisis has of course affected all regions of the UK.

The underfunding of healthcare and education is for once not immediately nor exclusively a party-political issue. Neither the Scottish Nationalist administration in Edinburgh nor the Conservative government in Westminster have managed to get to grips with these problems. They remain a consequence of the broader economic crisis which, after Covid and Brexit, the entire country is experiencing, and which has been exacerbated by national fiscal mismanagement. For that part at least, it may seem fair to apportion much of the blame to the actions and inaction of national government.

Once again, the British people are increasingly exasperated by the failures of one of the world’s richest states to provide safe, secure, and sustainable levels of essential public services. Yet it was of course those very same people who brought into power the successive administrations which have overseen this process of collapse. It was also that UK electorate which voted for Brexit, a major causative factor – according to most experts – behind the country’s current economic woes.

Rishi Sunak’s government was reported last month as considering the possibility of seeking to rebuild close economic ties with the European Union in a bid to reverse some of this damage. It was however swiftly warned off this sensible plan of action by the squawking voices of those Eurosceptical ideologues who dominate debate on the Conservative backbenches, and their allies in the populist right-wing media. That will come as a great relief to those monied interests which continue to profit nicely from the UK’s exclusion from smooth European trading arrangements, its reliance on more distant markets, and the collapse of the pound.

At the same time, it was reported that Britain’s net migration for the first half of this year had hit a record high, topping half a million people. This might be considered good news for those concerned about labour shortages, cultural diversity, and human rights, but it wasn’t welcomed by those in the Tory Party and the tabloid press whose xenophobia has informed the last decade of UK immigration policies.

The fact that many of these migrants were international students contributing many billions to the British economy in cash and skills did nothing to pacify those extremists whose strategies on asylum-seekers have included plans to fly them off to central Africa, while the chronic underinvestment in, and demotivation of, Home Office staff engaged in the processing of visa applications has led to massive backlogs of refugees filling detention camps stretched to far beyond their intended capacities.

Meanwhile, investigations have been launched into the culpability (and potential negligence) of French and British coastguard services following the emergence last month of new evidence relating to the deaths of twenty-seven people unlawfully crossing the English Channel a year ago.

Only last week, more asylum-seekers died when another small boat sank on its way to England from France.

While all this has been going on, the British government have developed plans to reverse regulatory safeguards imposed upon financial industries in an attempt to prevent a repeat of the excessive risk-taking that had led to the banking crash of 2008. On the same day this month that these ‘reforms’ were unveiled, it was reported that the UK’s financial watchdog had fined Santander more than £100 million for persistent failings in its money-laundering controls.

This column usually attempts to find the lighter side of the ongoing series of calamities that have recently come to characterise British political, economic, and social life. But there’s really nothing funny in any of this. I’m sorry, but I’m afraid there’s nothing much to laugh about here.

Alex Roberts

Alex Roberts

8 Min Read

8 Min Read