News from Nowhere: The Invisible Man

The era of photoshop makes it rather easier to airbrush our unwanted leaders from history.

The novelist Milan Kundera once wrote an account of a famous photograph of members of the committee who had then ruled his native Czechoslovakia. As wasn’t unusual in those days, the image of one former government minister had been expunged from the photograph. Yet, his discarded hat had remained on view. Some traces of the past remain impossible to erase.

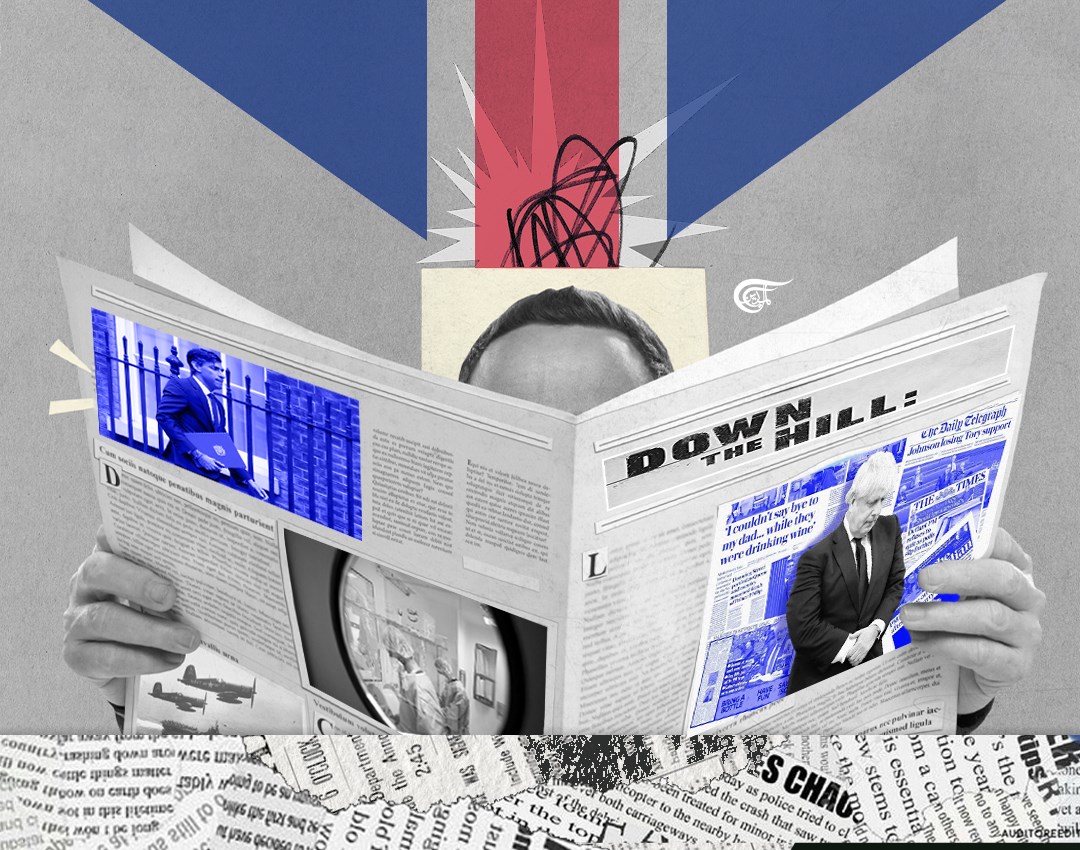

The era of photoshop makes it rather easier to airbrush our unwanted leaders from history. Earlier this month, the UK’s Business Secretary Grant Shapps tweeted a photo of himself visiting the UK’s new spaceport in 2021. Eagle-eyed observers were swift to point out that the original picture of Mr. Shapps meeting two spaceport managers had included a fourth figure, the then Prime Minister Boris Johnson.

A decade ago, the British Conservatives were embarrassed when it turned out that the picture of a group of their younger party members, which had featured in a set of promotional materials, was in truth a stock photo of Australian students. (They were tanned, fit, and smiling, and were therefore clearly not accurate representatives of the grim reality of our Tory youth.) In 2015, there were blue blushes once more when it transpired that a highway shown on a Conservative election poster promising a ‘road to a stronger economy’ wasn’t in the UK at all but was in fact in Germany.

Such things are hardly new. The art of image manipulation preceded the age of the deepfake by very many years. When promoting new military hardware, for example, it’s probably best to avoid using footage from Top Gun or generic backgrounds from digital wallpaper websites, as these techniques have caused red faces in the not-too-distant past.

In the era of rolling news and round-the-clock citizen scrutiny, someone somewhere out there is bound soon enough to catch you out. Welcome to the realm of what the former UK Communities Secretary Eric Pickles has called the army of armchair auditors.

(We may note that Mr. Pickles himself suffered some online ignominy a while back, as a result of a minor typo, when he mentioned on social media the popular high street store from which he bought his “shirts”... except that wasn’t quite what he said.)

Mr. Shapps has claimed to have been unaware that the controversial spaceport shot had been doctored. He’s been keen to distance himself from the idea that he had intended to purge from the archives any record of his association with his disgraced old boss.

That would however suggest that he had simply forgotten that he had been accompanied on his visit to Britain’s premier spaceport by a man who’d been Prime Minister at the time. One would have thought that most people might have remembered that.

Mr. Shapps has hardly developed a reputation for being very sharply and effectively focused on his ministerial responsibilities, but that particular instance of selective amnesia would sound rather remiss, even for him.

There may of course have been other, stranger reasons for this odd occurrence. It might have been that Boris Johnson himself had somehow (possibly deploying residual security service contacts) arranged to be removed from the photograph in uncannily prescient anticipation of this latest British flop, the unfortunate near-orbital event that was due to unfold. Although not as spectacular a failure as Liz Truss' brief but disastrous term in Downing Street, the attempted rocket launch earlier this month from Spaceport Cornwall – the first such effort in UK history – was hardly a resounding success.

Like Ms. Truss, it certainly didn’t live up to its media hype. And, like Liz Truss’ premiership, it crashed and burned.

Released from a jumbo jet over the Atlantic, the rocket malfunctioned and its entire payload of satellites, intended for delivery into planetary orbit, was lost.

One member of the public who’d visited the spaceport for the event told me how this historic moment had played out. “It had been a great atmosphere on the day,” he said. “It launched perfectly, but when we heard it had run out of fuel before hitting the stratosphere it was really disappointing.”

There are those who’d consider this comment offered a pretty apt description of recent British political history, of Liz Truss and Boris Johnson’s days in office, and those of their predecessors, and of their immediate successor.

The extent of the cumulative failings of the last dozen years of British government was partially demonstrated a fortnight ago, when it was revealed that more than 650,000 excess deaths (deaths above the average expected numbers) had been registered in the UK during 2022. It was reported that fewer than 40,000 of these had been related to Covid-19. It appears that the vast majority of these deaths resulted from the ongoing crisis in Britain’s healthcare system.

The current Prime Minister (as of writing) has attempted some very public interventions in order to be seen to be trying to resolve this situation, but these have as yet reaped minimal benefits. If Boris Johnson has now become the country’s invisible man, then Rishi Sunak’s starting to look like the man who wasn’t there – or at least the man who might as well not have been.

The bombastic Mr. Johnson's invisibility inevitably depends upon his absence, a quality honed to perfection during his holiday-strewn final weeks in office, a lame-duck leader gone missing in inaction. By contrast, the quietly ineffectual Mr. Sunak’s invisibility stems from his presence itself.

He has that much in common with the Leader of His Majesty’s Opposition. He’s rarely less visible than when he’s standing right there. His immediate presence conjures the paradox of what we might call an intrinsically deniable fact. It recalls the fundamental indeterminacy of Kundera’s hat or of Schrödinger’s cat. (Or, for that matter, of the redacted half of Moehringer’s latest book.)

It simultaneously signifies substance and lack. It’s about as easy to grasp as an eel in oil, or as Boris Johnson’s moral compass.

Rishi Sunak is about a week away from marking his first hundred days in office, that arbitrary but crucial period by the end of which a new leader is expected to have actually achieved something. But, as one commentator recently supposed in the influential right-wing journal The Spectator, he’s managed to do “very little” in that time and has more or less “wasted” his honeymoon months.

The new year had opened with the fresh-faced premier promising to fix the nation’s problems with a series of five key pledges, a trick straight out of Tony Blair’s 1997 electioneering playbook.

Sunak had vowed to reduce the national debt and grow the economy; objectives which look good on paper but which, at a time of high employment, offer only modest fare in the way of direct, tangible, and concrete impacts on the daily life of the average British person on the average British street.

Much to everyone’s surprise, the latest figures show that the UK economy grew very slightly in November. This appears to have been a consequence of the spending boost enjoyed by the hospitality industry during the World Cup. The British government may now consider calling FIFA to request they run another global tournament next month. They could even check with the IOC to see if they might manage an extra Olympics this spring. The new King’s coronation already has early summer covered.

Dishy Rishi Rich also pledged to “pass new laws to prevent small boats." One assumes that here he’s pandering to the common Tory preoccupation with unlawful attempts made by asylum-seekers to cross the English Channel, rather than proposing a general hostility toward undersized leisure craft – although one understands that multimillionaires in his class are often thought to favor the attractions of the so-called superyacht.

More importantly, he undertook to halve the rate of inflation within twelve months and to solve the crisis in the National Health Service, in a bid to ensure “people get the care they need."

During the festive period last month, the government had gone so far as to ask the public not to get too dangerously drunk, as the health service wouldn’t be able to cope with the increased demand. Overseas observers might consider this a reasonable (and in fact blindingly obvious) request, but those observers have clearly never seen what the British are like at Christmas. Asking people to avoid perilously excessive alcohol consumption in the second half of December seems almost as bad as bringing back wartime rationing to the planet’s proudest nation of inebriation.

(It would be like asking Boris Johnson – who’s already earned well over £1 million in the few months since he left office and taken another million by way of a donation from a friendly cryptocurrency investor – to lay off the luxuries. One big business benefactor has provided him with opulent accommodation, and he took a quarter of a million from a Chinese software company for a speech he recently made in Singapore. Despite his former colleagues’ understandable efforts to delete his memory from political history, his capacity for bullish bluster is continuing to pay off. It’s the modern equivalent of that old Czech politician’s hat. It just won’t go away.)

It was reported this month that by the end of last year, it took paramedics an average of ninety minutes to respond to emergency calls. As we’ve lurched into 2023, ambulances have continued to queue for hours outside hospitals with too few beds for their patients. And that’s on a good day. On other days, the paramedics or the nurses have been out on strike.

They’ve been striking along with the railway staff, the border officers, the postal workers, and many other key members of the public sector. No wonder we can’t get a rocket into space. We can’t even get a plane to Paris, a train to Truro, a parcel to Plymouth, or a letter to Leeds. Or even an ambulance or a cannula to wherever they’re supposed to go.

Alex Roberts

Alex Roberts

10 Min Read

10 Min Read