World's largest iceberg runs aground off heavily inhabited island

A23a is stuck around 70 kilometers from South Georgia Island, home to seals and penguins, pausing its 40-year journey from the Antarctic.

-

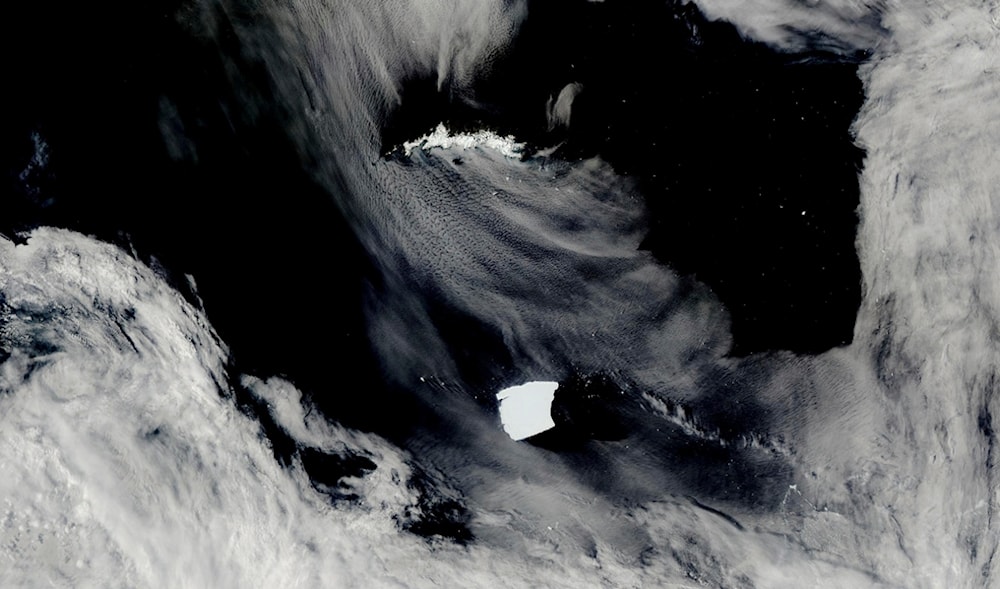

An iceberg seen on NASA’s Aqua satellite, known as A23a, center, is visible as it heads toward South Georgia Island, top, on January 15, 2025, off the coast of Antarctica. (NASA Worldview via AP)

The world’s largest iceberg, A23a, appears to have run aground about 70km from South Georgia island in the Atlantic Ocean, possibly sparing the vital wildlife habitat from disruption, according to researchers.

The massive iceberg, spanning roughly 3,300 sq km and weighing nearly one trillion tonnes, has been drifting north from Antarctica since breaking free in 2020.

Scientists had feared it could collide with the island or obstruct the feeding routes of penguins and seals. However, since March 1, it has remained stuck 73km away, which may prevent significant harm to local wildlife. While it remains uncertain whether A23a will stay grounded, its melting could enrich the ecosystem by releasing nutrients.

A23a originally calved from Antarctica in 1986 and remained stationary for over 30 years before resuming its slow drift. Although previous observations suggested it stayed intact, a 19 km chunk broke off in January. While it currently poses no risk to shipping, as it disintegrates, smaller ice fragments could create hazards for commercial fishing.

Moreover, South Georgia, home to millions of seals and breeding birds, was already hit hard after suffering from a bird flu outbreak.

How ice loss is already impacting the planet

Scientists warn that while massive icebergs are a natural part of Antarctica’s cycle, accelerating ice loss due to climate change could significantly impact global sea levels.

In 2023, scientists warned that the rapidly melting Antarctic ice could drastically reduce deep-water currents, which would have long-term effects on the distribution of fresh water, oxygen, and nutrients necessary for life.

Modeling shows that if global carbon emissions continue to be high, faster Antarctic ice melts will result in a "significant slowdown" of water circulation in the ocean depths, as per a report published in Nature.

Consequently, a study led by Australian researchers and published on March 4, 2025, corroborated the Nature report, warning that in a high-emissions scenario, the Antarctic Circumpolar Current—Earth’s strongest ocean current—could slow by 20% by 2050, worsening Antarctic ice melt and sea level rise.

This current, which connects the Atlantic, Pacific, and Indian Oceans, plays a key role in regulating heat and carbon dioxide in the ocean while keeping warm waters away from Antarctica.

The study found evidence of a "substantial reconfiguration of Southern Ocean dynamics," with "far-reaching impacts on global climate patterns, oceanic heat distribution, and marine ecosystems."

Co-author Assoc. Prof. Bishakhdatta Gayen from the University of Melbourne called the findings "quite alarming," explaining that as Antarctic ice melts, it releases cold, fresh water that spreads toward the equator, altering ocean density—a key factor in driving currents—and causing the slowdown.

Gayen warned that the ocean is a delicate system, saying that should this current "engine" fail, it could lead to increased climate extremes and faster global warming due to the ocean’s reduced ability to absorb carbon.

3 Min Read

3 Min Read