On Hitler’s economic beginnings: tariffs, nationalism, the road to war

In an opinion piece for the Atlantic, Timothy W. Ryback, alluding to the Trump administration's global tariff war, argues that Hitler’s early embrace of tariffs and economic nationalism was not just poor strategy, but a forewarning of war.

-

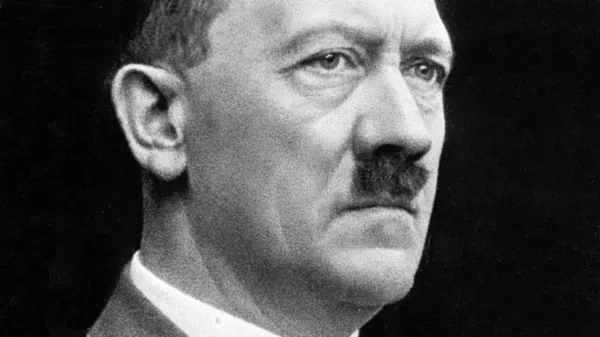

German Federal Archives / Adolf Hitler

In his Atlantic opinion piece, Timothy W. Ryback argues that tariffs and trade protectionism were key pillars of Adolf Hitler’s economic agenda from the moment he became chancellor in January 1933, drawing a subtle comparison to

German Federal Archives / Adolf Hitler

In his Atlantic opinion piece, Timothy W. Ryback argues that tariffs and trade protectionism were key pillars of Adolf Hitler’s economic agenda from the moment he became chancellor in January 1933, drawing a subtle comparison to

US President Donald Trump's tariff policies and their global impact.

Within 48 hours of Hitler taking office, key ministers in Nazi Germany were already pushing for higher agricultural tariffs and trade policy revisions. Hitler, according to Ryback, was primarily focused on avoiding “unacceptable unrest” ahead of the March 5 Reichstag elections, seeing economic stability as instrumental to his political consolidation.

Ryback speaks of Hitler’s lack of economic literacy and financial integrity, noting he owed 400,000 reichsmarks in back taxes, and cites his primitive understanding of inflation:

“You have inflation only if you want it,” Hitler once said. “Inflation is a lack of discipline. I will see to it that prices remain stable. I have my SA for that.” (The SA, or Brownshirts, were the original paramilitary organization associated with the Nazi Party.)

Ryback also notes Hitler’s reliance on Gottfried Feder, the Nazi Party’s chief economist, who had helped shape the original party platform blending socialism and nationalism. Feder, in Ryback’s analysis, was a staunch protectionist who believed that “National Socialism demands that the needs of German workers no longer be supplied by Soviet slaves, Chinese coolies, and Negroes.”

Feder’s position, Ryback writes, was clear: Germany should eliminate dependence on global trade and instead protect domestic production through “import restrictions”. Feder rejected both “the liberal world economy” and “the Marxist world economy,” advocating for economic self-reliance rooted in nationalist ideology.

Though figures like Foreign Minister Konstantin von Neurath warned of trade wars and surging prices, Ryback explains that Feder’s vision aligned with Hitler’s larger ideological goals, to "liberate" Germany from international systems and reassert control over national destiny.

Inherited recovery and rising tensions

Ryback stresses that Hitler inherited an economy already on the mend following the crash of 1929. He cites a December 1932 report from the German Institute for Economic Research stating the crisis had been “significantly overcome.”

The German stock market had rallied on news of his coming to power. “The Boerse recovered today from its weakness when it learned of Adolf Hitler’s appointment, an outright boom extending over the greater part of stocks,” The New York Times reported.

However, Ryback notes that optimism quickly waned as fears of a reckless, nationalistic economic strategy spread. Conservative voices, like the Centre Party and Eduard Hamm, warned Hitler against violating free market principles and abrogating international agreements.

Hamm explained that while Germany brought in more agricultural goods from its European neighbors than it sent out, those same countries served as important markets for Germany’s industrial exports:

“The maintenance of export relations to these countries is a mandatory requirement,” Hamm wrote. If one were to “strangle” trade through tariffs, it would endanger German industrial production, which, in turn, would lead to increased unemployment. “Exporting German goods provides three million workers with jobs,” Hamm wrote. The last thing Germany’s recovering but still-fragile economy needed was a trade war. Hamm urged Hitler to exercise “greatest caution” in his tariff policies.

Yet Hitler, as Ryback explains, refused to provide clarity or reassurance. Instead, he vaguely pledged in a national address, “Within four years, the German farmer must be saved from destitution,” Hitler said. “Within four years, unemployment must be completely overcome.”

By this time, Ryback points out, Hitler had already distanced himself from Feder, abandoning proposals for taxing the wealthy, state oversight of corporations, and restrictions on chain stores.

Ryback argues that Hitler deliberately avoided offering a coherent economic program, telling party leaders that “there is no economic program that could meet with the approval of such a large mass of voters,” referring to his securing an outright majority in the March 5 Reichstag elections. This, Ryback suggests, reflected a preference for political expediency over economic planning.

The Hitler tariffs and the backlash

On February 10, 1933, just two weeks into his chancellorship, Hitler imposed sweeping tariffs. Ryback notes these shocked the public and press alike, “The dimension of the tariff increases have in fact exceeded all expectations,” wrote the Vossische Zeitung. The New York Times called it simply “a trade war.”

Ryback details how these tariffs targeted key European partners, Scandinavia and the Netherlands, especially on agricultural and textile goods. Some tariffs rose by 500%. Denmark, whose livestock exports were suddenly blocked, faced severe economic fallout. In retaliation, Ryback writes, these countries threatened or imposed countermeasures. The Dutch warned their response would be felt as “palpable blows” to German exports.

Ryback reports that Hitler's foreign minister soon informed him that: “Our exports have shrunk significantly, and our relations to our neighboring countries are threatening to deteriorate.”

Trade with France, Sweden, Denmark, and Yugoslavia also began to fracture. Finance Minister Krosigk estimated that an additional 100 million reichsmarks would be needed in deficit spending to support agriculture alone.

Economic nationalism as prelude to war

Ryback draws attention to Hitler’s rally at Berlin’s Sportpalast the same evening the tariffs were announced. Donning his brownshirt uniform, Hitler framed his economic agenda within a broader vision of national revival and defiance of global systems: “Never believe in help from abroad, never on help from outside our own nation, our own people.”

Though he did not explicitly mention the tariffs or his rearmament plans, Ryback points out that Hitler had already told his cabinet that, “billions of reichsmarks are needed for rearmament... The future of Germany depends solely and exclusively on the rebuilding of the army.”

Ryback argues that the trade war was a deliberate, ideologically driven act, a preview of Hitler’s larger ambitions. The move away from economic cooperation, the demonization of foreign trade, and the authoritarian reordering of national priorities all signaled what was to come.

Ryback concludes that Hitler’s tariff regime was more than poor policy; it was a warning. It marked the beginning of a broader strategy to upend the international order and remake Germany into an autarkic and militarized power. The trade war, Ryback believes, foreshadowed the shooting war that would soon follow.

In his view, the tariffs exemplified how Hitler’s early economic policies, cloaked in nationalist rhetoric and enforced through authoritarian means, set the stage for both domestic upheaval and global conflict.

6 Min Read

6 Min Read