African countries scramble to stop the hemorrhaging triggered by Trump’s ‘ruthless’ health aid cut

From introducing new taxes to raising existing ones, budget revisions, and the search for new donors... Left in limbo by Trump’s sudden aid withdrawal, African countries scramble to sustain their health systems.

-

African countries scramble to adapt to Trump’s ‘ruthless’ health aid cut (Illustrated by Batoul Chamas; Al Mayadeen English)

As the rainy season starts in different parts of Africa this year, mosquitos will also be faithfully arriving in most homes to deliver malaria unlike anti-malaria bed nets, testing kits, and medicines that won’t be arriving, because the United States government has suddenly cut a $90 million contract to a firm that supplies the equipment and consumables that would have protected 53 million people in 14 most malaria-prone African countries. As a result, more pregnant mothers and children under five are expected to die from the fatal disease.

The same fate could be also waiting for the tens of millions of Africans already living with HIV/Aids and those at risk of contracting the virus, as well as others at risk of tuberculosis, Ebola, and other preventable and treatable diseases, such as polio.

From Zimbabwe to Uganda, from Mozambique to Ghana, from Chad to Angola, across all Africa, governments are scrambling to come up with urgent measures to plug the huge health funding gaps caused by the United States’ aid cut. This move, coupled with Donald Trump’s decision to withdraw the US from the World Health Organization (WHO), has thrown the health systems of most African countries into turmoil. With 22 of the world’s 26 poorest countries being found on the African continent, the continent is overly dependent on aid for its healthcare, and the sudden cut by the US – until now the biggest healthcare donor – is having catastrophic effects.

‘Ruthless and callous decision’

Experts point out that while it is the prerogative of the US government and its citizens to decide how to allocate their funds, the peremptory and seemingly vindictive nature of the cuts is cruel, especially since the countries are heavily reliant on US assistance and are left without a chance to adjust.

The sudden withdrawal led WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus to emphasize that the United States “has a responsibility to ensure that if it withdraws direct funding for countries, it’s done in an orderly and humane way that allows them to find alternative sources of funding.”

Caritas Internationalis, a Vatican-based confederation of 162 Catholic relief, development, and social services organisations working in more than 200 countries, also protested against the abrupt manner in which the cuts came.

“The ruthless and chaotic way this callous decision is being implemented threatens the lives and dignity of millions," Caritas said in a statement.

USAid spent over $12 billion in sub-Saharan Africa in 2024, according to government records, most of it on health-related programs. In 2022, of the $5.8 billion the US committed to Africa’s health programmes, a lion’s share of $3.8 billion went toward HIV/AIDS programmes, $687 million to fighting malaria, $385 million to maternal and child health, $340 million to family planning and reproductive health, $220 million to water supply and sanitation, $160 million to Global Health Security in Development, $126 million to TB prevention and treatment, and $106 million to nutrition programmes.

Unfolding health crises

Fears of increased deaths are now growing in Eswatini, Zimbabwe, Zambia, Malawi, Lesotho, Mozambique, and other southern African countries that not only have severely underfunded healthcare systems but also have substantial segments of their populations living with HIV virus.

WHO has warned that eight countries – Haiti, Kenya, Lesotho, South Sudan, Burkina Faso, Mali, Nigeria and Ukraine – risk exhausting their supplies of HIV treatments in the coming months.

“People will die,” said Dr. Catherine Kyobutungi, executive director of the African Population and Health Research Centre, “but we will never know, because even the programs designed to count the dead have been cut.”

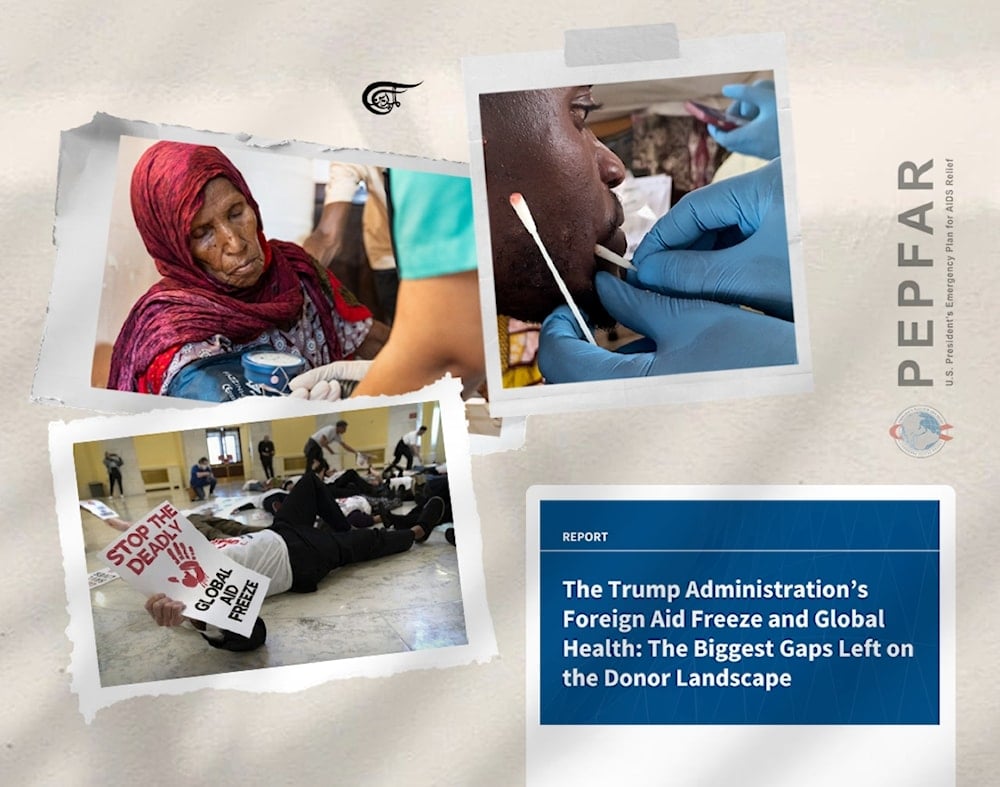

Through a 22-year old President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) programme, the US has provided life-saving antiretroviral (ARV) treatment to more than 25 million people in Africa. With more than eight million in South Africa living with HIV, PEPFAR has been contributing 17% of the country’s $2.3 billion annual cost of providing ARVs to 5.5 million people. Fortunately, unlike other countries, 74% of South Africa’s HIV treatment is funded through the government's own resources, making it less vulnerable to the aid cut shocks.

Zimbabwe – a country with 1.2 million people on ARV treatment – has received about $200 million annually from the PEPFAR. In addition to paying for ARVs, the PEPFAR funds have supported salaries and incentives for healthcare workers in the country, in addition to funding HIV and viral load testing, prevention, cervical cancer screening, and tuberculosis treatment.

However, with 98% of the country’s medicines bill being paid by donors, the effect of the US aid freeze would be cathartic. Health minister Douglas Mombeshora admitted that the cancelled funding would be felt.

“The funding gap that has been created is huge,” he said in a press conference. “We are talking about $300 and $400 million and we are working toward covering that gap gradually.”

The Zimbabwean government had set aside $786 million for the Health ministry in its 2025 budget as between 40% and 55% of the country’s health budget has traditionally come from donors.

Strained finances

Analysts warn that filling the void left by the US departure is a big ask for the strained finances of many governments — many African countries spend more on servicing debt than health. The continent has more than $1.2 trillion in external debt, with the debt-to-gross domestic product ratio rising by about two-fifths since 2008, according to the African Export-Import Bank.

Even South Africa, one of the well-off economies on the African continent, is also struggling with budgetary adjustments to make up for the shortfall caused by the US aid cut.

The country budget presentation had to be postponed twice after Finance Minister Enoch Godongwana proposed an increase in consumption tax – called Value Added Tax (VAT) – in order to raise an additional 28.9 billion rand ($1.5 billion) needed to fill the gap caused by the cut. The money would go toward paying the salaries of some 9,300 medical personnel in clinics and hospitals and about 800 newly qualified doctors. The increased tax is also meant to progressively grow the country’s health budget from 277 billion rand ($15 billion) in 2024/25 to 299 billion ($16.3 billion) in the 2025/26 year and to 329 billion rand ($17.8 billion) in 2027/28.

On its part, Zimbabwe’s ministry of Health is preparing a supplementary budget to raise additional funds to fill the gap. The country, which for decades has collected AIDS levy from workers but diverted the funds to other uses, is hoping to mobilize extra resources from newly introduced taxes on sugar, airtime, and fast foods.

Community Working Group on Health Director Itai Rusike says the timing of the funding withdrawal is particularly concerning, given Zimbabwe’s current economic constraints and competing priorities.

“Given the very significant role that USAid has been playing in the past, not just in the health sector, but also in the social sectors, it will leave a huge financing gap the Government of Zimbabwe would have to fill,” Rusike said. He wants the Ministry of Finance to ring-fence the sugar tax, airtime tax, and AIDS levy to exclusively go toward health. “Without immediate action to mobilise replacement funds, the consequences could be dire,” Rusike concluded.

Nigeria, a country with about 1.8 million citizens living with HIV, is also scrambling to raise an extra $1 billion for its health care. The African continent’s most populous nation of 236 million people also accounts for the world’s highest number of malaria deaths and ranks among the top countries for tuberculosis cases. The Nigerian Federal Executive Council, which is mobilizing funds to fill the shortfall, says the new funding will support improvements in primary healthcare services, maternal and child healthcare, and the training of healthcare professionals, among other projects previously funded by the US.

Ghana has also started mobilizing local resources to fill in the $78.2 million shortfall in its health sector after the US cut $156 million in funding to Accra, according to presidential spokesman Felix Kwakye Ofosu.

Lesotho’s Health Minister Selibe Mochoboroane claims that the tiny country of 2.4 million will need only R181-million ($10 million) to cover the shortfall if the US government decides to cut R1.2-billion ($66 million) in HIV funding. Mochoboroane told his country’s parliament that PEPFAR’s approach is “too expensive” and that the government must “adopt methods that align with our available resources”.

Nebulous fundraising strategies

While many leaders across Africa have described Trump’s decision to abruptly end billions of dollars in aid to the continent as a wakeup call for greater self-reliance, most countries still lack clear strategies to address the challenge, with many leaders appearing to be in a state of denial or shock.

Zambian President Hakainde Hichilema, whose country was receiving $600 million in aid annually from the US, thanked Trump for the decision but has not provided any details on how his government – currently strengthening ties with China – plans to fill the gap.

President Yoweri Museveni of Uganda – another country most reliant on US aid – told his people not to worry about the Trump cuts but has avoided explaining how he plans to make up for the huge shortfall.

“It would be really good to see people, instead of just talking, saying what is their long-term plan to replace aid,” said Nic Cheeseman, a professor of democracy at the University of Birmingham. “What we haven’t seen so far from leaders is anything that remotely resembles a strategy,” he added, noting that many countries have done little to finance their own health care and other needs over the decades.

Cyril Zenda

Cyril Zenda

9 Min Read

9 Min Read