Classified Documents Cast Doubt on U.S. Assurances for Assange

When the U.S. says Assange can serve any potential sentence in Australia— that doesn’t really guarantee anything.

-

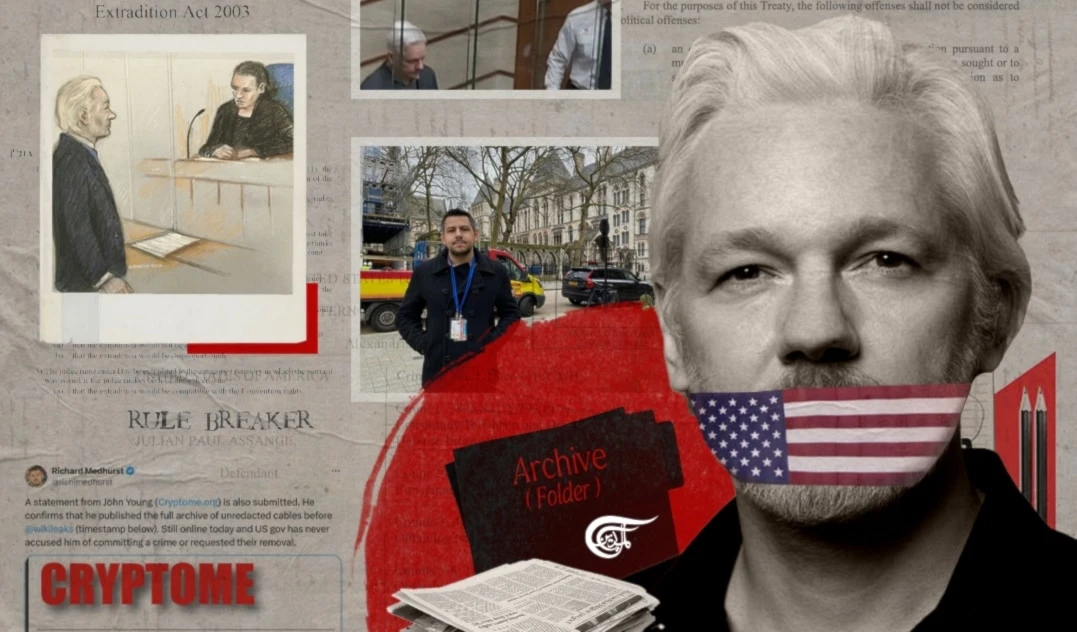

Classified Documents Cast Doubt on U.S. Assurances for Assange

I have covered Julian Assange's extradition battle since 2020. The United States is attempting to extradite the Australian journalist and WikiLeaks founder after he published classified documents, which revealed evidence of U.S. war crimes in Iraq and Afghanistan, in addition to diplomatic cables from the U.S. State Department.

In January, Judge Baraitser blocked Assange’s extradition on health grounds; she found U.S. prison conditions to be too oppressive, which could lead him to commit suicide. In October, the United States appealed this decision on five grounds.

This morning, I attended remotely as the High Court in London delivered its judgement, ruling in favor of the US. The United States was denied appeal on grounds pertaining to Assange’s health, but the Court accepted its diplomatic assurances.

The United States has offered a package of assurances which appear to say that Assange won’t face confinement at ADX Florence or under oppressive prison conditions, known as Special Administrative Measures (SAMs). They also say he could serve a potential sentence in his home country Australia.

The ruling issued today by the High Court was based on the premise that US assurances can be trusted. Classified documents that I obtained show this to be wholly untrue.

The case of David Mendoza Herrarte

In 2009, the United States extradited David Mendoza Herrarte from Spain to the United States for drug trafficking. The U.S. also provided diplomatic assurances for Mendoza— assurances which it broke, as documents show. Mendoza’s case was cited by Assange’s lawyers at the High Court as evidence that U.S. assurances cannot be trusted.

Mendoza is an American and Spanish national. He left the United States in 2006 and resettled in Spain after learning U.S. authorities were on to him. Two years later in June 2008, he was arrested by Spanish authorities under an international arrest warrant. The United States requested his extradition, however, because Mendoza was now living in Spain, married and with children, the Spanish National Court (Audiencia Nacional) imposed three conditions on his extradition to the U.S.:

1. Mendoza must serve any US-imposed sentence in Spain

2. He cannot be given a life sentence or similar term of confinement (life sentences are forbidden in Spain)

3. He cannot be tried for currency structuring (as this is not a crime in Spain)

-

Spanish National Court rulings from August and November 2008 stipulating the conditions of Mendoza’s extradition to the United States, and Spain’s right to impose conditions on extraditions under the U.S.-Spain Extradition Treaty

Spanish courts issued two rulings in August and November 2008, clearly stipulating these requirements, and reiterating that Spain did have the right to impose conditions on the extraditions of Spanish nationals to the U.S.

In January 2009, the United States Embassy in Madrid sent the following, unsolicited diplomatic assurance to the Spanish government.

-

Verbal note sent from the U.S. Embassy in Madrid to the Spanish government, containing diplomatic assurances regarding David Mendoza, January 2009

Note the wording. It says the U.S. does not object to Mendoza “making an application to serve his sentence in Spain”. This is clearly not the same as: we will allow Mendoza to return to serve his sentence in Spain, for example.

Regarding the life sentence, the diplomatic note said the U.S. “will not seek a sentence of life imprisonment”, however, that it “will do everything within its power, that Mendoza receives a determinate sentence of incarceration”.

A “determinate sentence of incarceration” could mean any number of years behind bars. The U.S. could impose a sentence of 200 years imprisonment, for example, and then claim it’s technically not a life sentence because it doesn't say “life”— not an unusual practice in the U.S.

The diplomatic note also listed all the charges brought against Mendoza— including the currency structuring charge, despite this being explicitly ruled out by the Spanish Court.

Mendoza and his attorney were alarmed by the ambiguity of the note. They took it to court, which resulted in a ruling, stipulating that the Spanish government and police must do everything within their power to make sure the U.S. respects the conditions of Mendoza’s extradition. The result was a contract called the “Acta de Entrega” or “Deed of Surrender”.

-

The original Acta de Entrega: a contract between Mendoza, the United States and Spain, stipulating that his extradition comply with the conditions imposed by the National Criminal Court. All three signatures are visible: the Spanish government’s, David Mendoza’s and the United States’ (represented by Kimberly Wise), April 2009

This Acta de Entrega (Deed of Surrender) was signed April 30, 2009, the day of Mendoza’s extradition. To avoid any misunderstanding the last sentence says: “signing those present as proof of agreement.” followed by three signatures: the Spanish government, David Mendoza, and Kimberly Wise.

-

Kimberly Wise, who signed the Acta de Entrega on behalf of the United States, can be seen working at the U.S. embassy in Madrid as recently as 2019

Kimberly Wise works at the U.S. embassy in Madrid; she signed this contract on behalf of the U.S. government, which clearly says David Mendoza is surrendered to the U.S. authorities “In accordance with what was previously stipulated by Section Two of the National Criminal Court”, i.e., the U.S. must allow Mendoza to serve his sentence in Spain, mustn’t give him a life sentence, nor try him for currency structuring.

-

Official English translation of the Acta de Entrega or “Deed of Surrender”: a contract between Spain, David Mendoza, and the United States.

Mendoza was extradited to the U.S. in April 2009, and subsequently sentenced to 14 years imprisonment. When I interviewed Mendoza, he told me that during sentencing, he asked the court to respect the conditions of his extradition and send him back to Spain. The judge, Thomas Zilly, told Mendoza that he had no right to make any claims, because he wasn’t a signatory of the U.S.-Spain Extradition Treaty.

That might sound like a ridiculous statement because it is. Obviously, Mendoza isn’t a signatory—treaties are signed between countries, not natural persons. Nevertheless, this was the judge’s logic. Mendoza was told to go to prison and make a treaty transfer application from there. He did and waited seven months for a response. In July 2010 the Department of Justice wrote back, denying his request for a transfer to Spain.

-

Document from the US Department of Justice denying David Mendoza’s application, July 2010

In total, Mendoza applied three times for treaty transfer to Spain, and each time his application was denied. The United States did this in violation of its diplomatic assurances and agreement with Spain.

After the first denial, Mendoza realized the US wasn’t going to give him any justice, so he decided to sue Spain. In 2014, Mendoza filed two lawsuits against Spain at the Spanish Supreme Court: the first for violating the conditions of his extradition, and the second for violating his human rights. Mendoza won both cases.

-

Spanish Supreme Court rules in Mendoza’s favor, December 2014

The Spanish Supreme Court effectively threatened to suspend the U.S.-Spain Extradition Treaty. Mendoza believes this is when the U.S. finally began to feel some pressure.

At the same time, Mendoza was writing to judges, MPs, lawyers, and others all over Spain— anyone he could get to pay attention. A judge sympathetic to his case anonymously sent Mendoza a copy of the Acta de Entrega— the contract he signed together with Spain and the U.S. the day of his extradition, stipulating his return.

Mendoza had previously attempted to retrieve this document through a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request. The U.S. refused to give it to him, saying it was classified, and that he wasn’t privy to diplomatic communications. Instead, they gave him a copy without his signature— essentially useless in court because he wouldn’t be able to sue the United States for breach of contract or non-compliance.

-

Under a FOIA request, Mendoza asked for a copy of the Acta de Entrega he signed (left). The U.S. denied his request, saying it was classified and that he was not privy to diplomatic communications. They instead gave him a copy without his signature (right)

Now that Mendoza finally had a copy, he went to civil court in the U.S. and sued the Department of Justice and Obama's Attorney General Eric Holder. Mendoza tells me this was so he could retrieve all the property the U.S. government took from him in seizures and forfeitures (around $14 million in various assets). At an arbitration hearing, Mendoza was originally promised that if he gave up a certain building in Tacoma, WA— itself worth millions— the U.S. wouldn’t oppose his treaty transfer. This proved to be untrue.

-

David Mendoza’s civil suit against the United States Department of Justice and Attorney General Eric Holder for breaching the conditions of his extradition from Spain to the United States, March 2014

I spoke with Alexey Tarasov, Mendoza’s lawyer in the U.S. who filed the suit against the DoJ. Tarasov recalls how U.S. prosecutors in Seattle phoned him up one day to say that if they dropped the civil suit, Mendoza could go back to Spain. Mendoza reluctantly accepted; he told me, “It’s the biggest regret of my life.”

Mendoza was extradited in 2009, but his transfer to Spain was only approved in 2015. At this point the U.S. had kept him for 6 years and 9 months in various prisons, violating its diplomatic assurances and contract with Spain. Only after suing both Spain and the United States was Mendoza finally allowed to return.

Back to Assange

In the case of Julian Assange, who's also been given similar diplomatic assurances: would he be as lucky as Mendoza? Mendoza tells me that’s highly unlikely.

For one, the diplomatic assurances don’t actually guarantee that Assange won't be placed in oppressive prison conditions (SAMs). They say Assange won’t be placed put in SAMs unless “in the event that, after entry of this assurance, he was to commit any future act that met the test for the imposition of a SAM.”

Mendoza told me this is not really an assurance, it’s an assurance with a back door. Once Assange is in the U.S., they could easily claim he did something that “meets the test for an imposition of a SAM”, put him in isolation, and say they never broke any promises. Just like the assurances they gave him, the ones for Assange are so vague, they’re hardly assuring at all.

When the U.S. says Assange can serve any potential sentence in Australia— that doesn’t really guarantee anything either. Australia must also accept the transfer in writing, as required under the Convention on the Transfer of Sentenced Persons. So far, it’s done no such thing, as I can attest to having covered the court proceedings.

Mendoza explained: Australia is a “Five Eyes” country. The US could simply to talk to Australia through backchannels and tell them not to take Assange—leaving him with no real guarantee that he could serve any US-imposed sentence in his home country.

Speaking to Mendoza following today’s judgement, he told me that if the U.S. violates its assurances and Assange tries contesting this in court, the courts will say that Assange is not a signatory of the UK-US Extradition Treaty and therefore has no claim, because he and the U.S. didn't sign anything together.

The United Kingdom, on the other hand, could make a claim. Assange would have to pressure the United Kingdom to pressure the U.S.— just as Mendoza had to pressure Spain to pressure the U.S. How likely is it, however, that Assange could successfully lobby the British to pressure the Americans into upholding the conditions of his extradition?

When the lead prosecutor James Lewis said the U.S. “have never broken a diplomatic assurance, ever”, this is simply untrue, as the documents above show. Even if the United States did issue an explicit assurance never to put Assange in ADX Florence or in SAMs, and to do everything in its power to make sure he serves a sentence in Australia— could it be trusted? The United States did sign a very explicit contract with Spain in exchange for Mendoza and didn’t keep its word then.

Mendoza feels that these “assurances” are not really assurances, but a way for the United States to game the legal system, deceive foreign judges, then do as it pleases once Assange is in U.S. jurisdiction. He recalls the countless Spaniards, Mexicans, Colombians, and others he saw extradited to the U.S. in similar ways. Once in America, who could force the U.S. to uphold the conditions of Assange’s extradition, or anyone else’s for that matter? Mendoza added: “I’m a nobody. If the United States did that to me, what are they going to do to Julian Assange?”

I attended Assange’s bail hearing remotely in January. Despite winning the case two days earlier, his bail was denied. Prosecutors argued that because of his past behavior i.e., taking refuge in the Ecuadorian embassy, that he couldn’t be trusted to show up to future court dates. (It’s highly contentious whether seeking political asylum— any given person’s right under international law— can be considered “bail jumping”). Nevertheless, the judge deemed Assange a flight risk because of his past behavior and denied him bail.

Today’s High Court ruling begs the question: if Assange was denied bail due to his past behavior, how can the Court reconcile the assurances offered by the United States with its history of violating them?

-

David Mendoza Herrarte with his two sons after being allowed to return to Spain from the U.S.

Richard Medhurst

Richard Medhurst

12 Min Read

12 Min Read