Still America first?

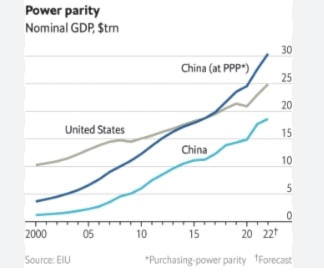

Measured with a more sophisticated indicator: the "purchasing power parity," the Chinese economy appears to be far bigger than the US’.

-

by the year 2030, the two largest economies in the world will be China and India, relegating the United States to third place (Illustrated by Batoul Chamas; Al Mayadeen English)

The leadership of the United States, both its governmental officials and its businessmen, intellectuals and the tycoons of the media, do not cease to preach urbi et orbi that this country has the largest economy on the planet and, therefore, still keeps the conditions needed to be the undisputed leader of the world, capable of delivering lectures to all others on issues, such as democracy, human rights, public freedoms, effective macroeconomic governance, and the rule of law.

But the reality is quite different and both self-reassured assertions are inconsistent with the empirical record. Regarding the size of the US economy, it all depends on the method of measurement. If you measure its size in US dollars, the American economy is still the largest one on earth, although its gap with the economy of the People's Republic of China has narrowed significantly in recent years. But if measured with a more sophisticated indicator: the "purchasing power parity," which calculates what a consumer can buy with a given amount of US dollars, the outcome is very different and the Chinese economy appears to be far bigger than that of the United States. The following table elaborated by the Economist Intelligence Unit, unsuspected of sympathies with the communist government of China, speaks for itself.

As can be seen, in 2018, the Chinese economy outperformed the US economy, and the observed trends anticipate that this gap will only widen in the future. In addition, an estimate made by Visual Capitalist based on official IMF data shows that by the year 2030, the two largest economies in the world will be China and India, relegating the United States to third place.

These data have not received the attention they deserve from conservative organizations, such as the IMF or the World Bank, given their global impact (that both organizations prefer to conceal) on the world economy and international geopolitics. We will not dwell on this analysis now, as it would divert us from our main argument, but we did not want something as important as this trend to pass completely unnoticed.

But size is only one aspect to consider when assessing the health of an economy. A very important dimension, often overlooked, is the weight of a state's public debt. In recent days, news came from the US Treasury Department saying that the federal government's total public debt has reached $34 trillion for the first time in US history. Of course, public debt has been a constant in the functioning of capitalist states. But in recent times, it has acquired a dimension that raises serious doubts about the pernicious effects of this state of affairs, especially when the debt grows uncontrolled.

In the case of the United States, a 2022 IMF report proves that the US public debt already far exceeds the size of its GDP. It does not reach the extremes of Japan, which had the highest general government debt-to-GDP ratio of the countries for which the IMF had available data: 261.3%. Next was Greece, with a reading of 177.4%. The US was fifth with a debt-to-GDP ratio of 121.4%. Argentina has a public debt amounting to 305 billion dollars. In relative terms, this value represents 80.62% of its gross domestic product. Even though in this sense, its situation is not as serious as that of Japan and Greece, the Argentine case is permanently on the front pages of the worldwide economic press. In other words, the US economy is afflicted by a structural weakness that constitutes, as Samir Amin used to remark, its incurable Achilles' heel: an economy running an unstoppable public deficit that largely exceeds its GNP, which explains its declining weight in the world economy, and the vigor with which a multipolar world - led by China, Russia, India, and Brazil, among others - has burst with unheard of strength onto the international scene.

The indebtedness of the American state reproduces within the US the same negative side effects observed in Third World countries: cutbacks in social "expenditures" (in reality, investments in health, education, and social security) and a relaxation of the budgets destined to fight climate change and protect the environment. Public debt exacerbates a country's economic problems by adopting policies of fiscal austerity that cause deeper economic downturns, creating more significant deficits and, ultimately, more debt. Debt and debt servicing costs force policymakers to make painful choices, a particularly problematic situation when the United States maintains exceptional spending and engages in numerous wars in third countries, which it has been doing without raising taxes, but rather reducing the tax burden on the wealthiest decile of the population while defraying the astronomical military expenditure by selling treasury bonds. As a result, the current wars have been paid for almost entirely with borrowed money, on which interest has to be paid. Through FY2022, the US government owes over $1 trillion in interest on these wars. The enormous growth of finance capital and its exorbitant profits is explained less by the general prosperity of the US economy than by the phenomenal military expenditures of a country that has not stopped fighting wars since the end of World War II and the political necessity of its successive governments to incur these enormous expenditures without raising taxes and alienating public opinion.

Finally, these expenses incurred by the military adventures of US imperialism end up plunging the countries of the Global South into misery, since the FED policies of rising interest rates create new circuits of appropriation of the economic surplus on the periphery of the system. The 2022 edition of the World Bank's “International Debt Report” proved that when global interest rates rose the most in four decades, developing countries spent a record 443.5 billion dollars on servicing their publicly guaranteed external debt. At the end of the story, American warmongering not only destroys the countries that are victims of its attacks, but also those that are not victims but must pay more, much more, for the debts contracted by their governments and to the detriment of the satisfaction of basic needs of their populations.

Atilio A. Boron

Atilio A. Boron

6 Min Read

6 Min Read