A German woman guarding the heritage of Palestine and Syria in Damascus

She has a distinguished appearance, as she sometimes wears around her neck a large necklace woven of colored threads or a shawl embroidered with Palestinian inscriptions.

Most of the residents of Old Damascus, specifically those who live in the Bab Sharqi neighborhood, know Mrs. Heike Weber.

The woman who has lived in Damascus for 40 years has a distinguished appearance, as she sometimes wears around her neck a large necklace woven of colored threads or a shawl embroidered with Palestinian inscriptions.

Despite the war and the emigration of her three children, Weber insists on staying in the city she loved, especially in her house, which she decorated according to her own taste, faithfully preserving the character of the traditional Damascene house.

From West Berlin ... the story began

In 1967, Weber was sixteen years old. At the time, she did not know the truth about what was happening in the Arab world. She told Al Mayadeen English, "The Israeli propaganda was falsifying all the facts, and at that time, our generation was interested in politics because of the problems between the two parts of East and West Germany, from which I come."

When the student movement was launched in West Berlin, Weber began to see things from a different perspective.

During her studies of music and comparative literature and her participation in student activities, she met Palestinian film director Jibril Awad, one of the cadres of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine, and the owner of the movie "Berlin the Trap," and they got married later.

She said, "We arrived in Beirut in 1982 and filmed a movie about what we witnessed in the Lebanese civil war, but in the end, we left for the Syrian city of Tartous, on board a ship that was carrying leftists belonging to the Palestinian Resistance, and George Habash was with us... I felt very sad at the time ... I loved Beirut, although I did not visit it before the war."

By handcraft, we create life and defeat death

In Damascus, it was not easy for the German young woman to start over and learn the Arabic language, but she wanted to get to know people and talk to them. In this context, she told Al Mayadeen English, "I decided to invest my passion in knitting, embroidery, and designing clothes, recalling what I learned from my grandmother. I started learning handicrafts at the age of four in my family's house in Germany because my generation and previous generations had to learn these things."

Weber admired and learned how to sew traditional dresses with the help of her Palestinian mother-in-law in the Yarmouk camp in Damascus. She also discovered the heritage battle that the Palestinians are waging against the Israeli occupation's attempts to steal Arab heritage. She said, "The Palestinians were very skilled in preserving the Palestinian identity by preserving the Palestinian embroidery, as today it reflects the interdependence between Palestinians at home and in the diaspora. It is nice that the Palestinian dress has become a symbol of the just cause."

Over the following years, Weber visited most of Syria and spent days and nights delving into the mythological meanings of every inscription, embroidery, and drawing. At one glance, she was able to distinguish between a piece woven by the hand of a woman from a village south of Aleppo and a piece woven by another woman from Al-Quds or Gaza.

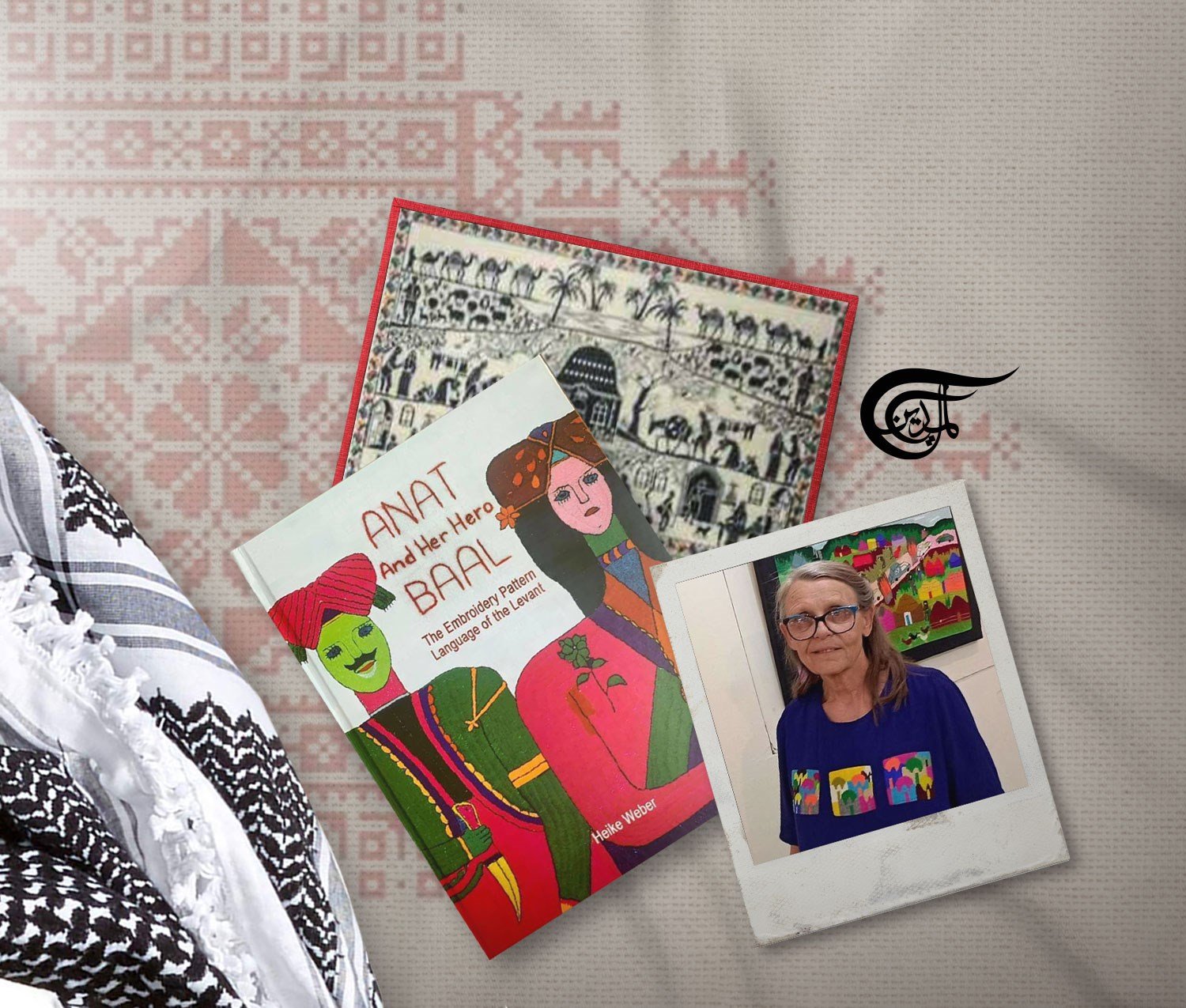

In the late eighties, Weber established her brand, in which she worked on designing fashionable clothes, in a Syrian spirit, and in cooperation with Syrian and Palestinian workers from the countryside and the city. She worked on teaching them and then employing them in production. So she explained to us, "I chose the name Anat for my brand because Anat refers to the gods who give life in ancient myths. Through this, I wanted to say that death is not the end, and after every death, there is a new beginning, and this is exactly the essence of manual work, as through it we create life, we defeat death."

Many foreign officials and celebrities visited Heike Weber's workshop in Damascus, including Queen Sofia of Spain, who visited her twice, as well as Queen Noor, wife of the late Jordanian King Hussein bin Talal, the wife of Turkish President Erdogan, and many others.

But the war changed everything, as she lost her workshop and lost contact with most of the women who used to work with her, knowing that they numbered more than a thousand women from various Syrian villages and Palestinian camps in Syria. She said, "I tried to communicate with them, but the circumstances of war, death, displacement, and others were stronger. Today I have the phone numbers of less than twenty women."

Forty years-experience in a book

Weber collected her forty years of research and experience on embroidery in a book she published in English titled "ANAT And Her Hero BAAL: The Embroidery Pattern Language of the Levant".

About this, she said, "Heritage embroidery is not only important to Arabs, but it is rather a global human affair, and I will soon publish my book in Arabic, to be available to every Arab looking for the origins and stories of his heritage."

She concluded by saying, "I love Syria, and I am happy that I am one of those who have contributed to documenting its heritage and identity." She fell silent for a few seconds and added, "When I die... burn my body and throw the ashes from the top of Mount Qasioun."

Sara Salloum

Sara Salloum

5 Min Read

5 Min Read