Tears once a year

Pasquale Liguori critiques the hypocrisy of Western media and audiences who consume award-winning images of Gaza's genocide as emotional tokens, void of political consequence or moral action.

-

The prize awarded to this photograph, like last year’s award for the so-called “Pietà of Gaza”, is plausibly a token gesture, a facade of political charity. (Al Mayadeen English; Illustrated by Batoul Chamas)

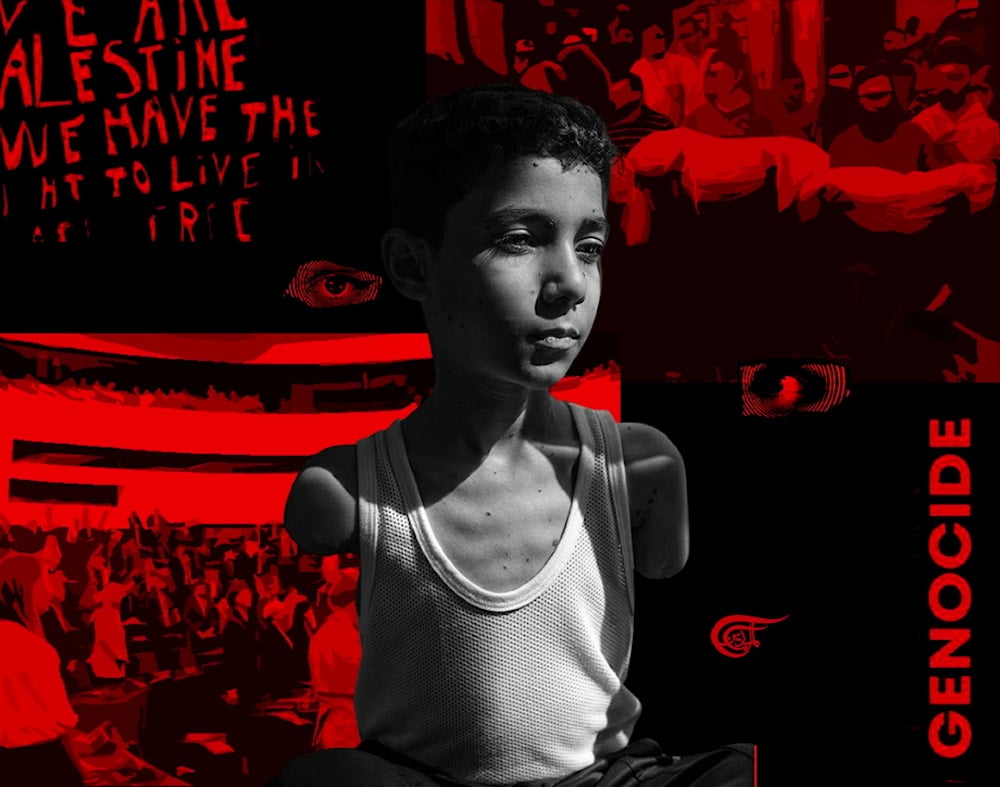

Those who refuse, or choose to distance themselves from, the filtered and distorted narrative crafted by mainstream media, in pursuit of a clear-sighted understanding of the events in Gaza, are confronted daily with a harrowing and overwhelming visual sequence. The bodies of children torn apart by bombs, organs spilled onto the asphalt, shattered skulls, broken limbs protruding from mangled flesh, charred and dust-covered corpses with hair soaked in blood; Dozens upon dozens of white bags filled with bodies, tightly bundled sheets containing human remains gathered like refuse; Flames consuming lives still conscious; Hunger, thirst.

This is the unequivocal documentation of the genocide underway, and the image of little Mahmoud—awarded World Press Photo of the Year 2024—fits seamlessly into this relentless stream of horror, largely censored by the puppet masters of disinformation, and conveniently ignored by liberal puppets with low thresholds for “sensitivity,” for whom five minutes from a power-aligned news anchor during dinner are, all in all, sufficient.

The prize awarded to this photograph, like last year’s award for the so-called “Pietà of Gaza”, is plausibly a token gesture, a facade of political charity handed out by a foundation based in Amsterdam, supported by prominent multinational firms specializing in strategic and legal consultancy for business and finance, whose products are consumed primarily by a Western audience. Nevertheless, through its media circulation, the image has the effect of reinforcing an annual commemoration of hypocrisy, when, in essence, the public is indifferent, desensitized, and/or shielded by the geographic distance separating them from the site of the crime. This is evident from the many social media comments circulating in recent days: systematic brutality is absorbed through a kind of functional neutrality, filtered again by the very hegemonic media that shape a pseudo-collective awareness of the issue. Thus, to be outraged or moved semel in anno—once a year—or occasionally by an award-winning photograph is not empathy, but a genuine act of disowning responsibility.

The photo of little Mahmoud, the work of a skilled photojournalist, likewise becomes part of a form of instant consumption: an emotional ritual blending spikes of fleeting commotion with even detached debates about the technical and stylistic qualities of the image. The image is observed, perhaps even cried over, analyzed, dissected, shared, and then swiftly forgotten, providing a sense of comfortable relief from any moral or political obligation to take concrete action.

The compassion these images may stir, if not translated into determined positions, political pressure, and a rejection of complicity (in weapons, alliances, narratives), is utterly meaningless. And so, photographs that remain “beautiful” in their tragedy are reduced to mere ornaments of bourgeois regret: Ultimately, just what the system wants, even through its so-called “awards.”

Pasquale Liguori

Pasquale Liguori

3 Min Read

3 Min Read