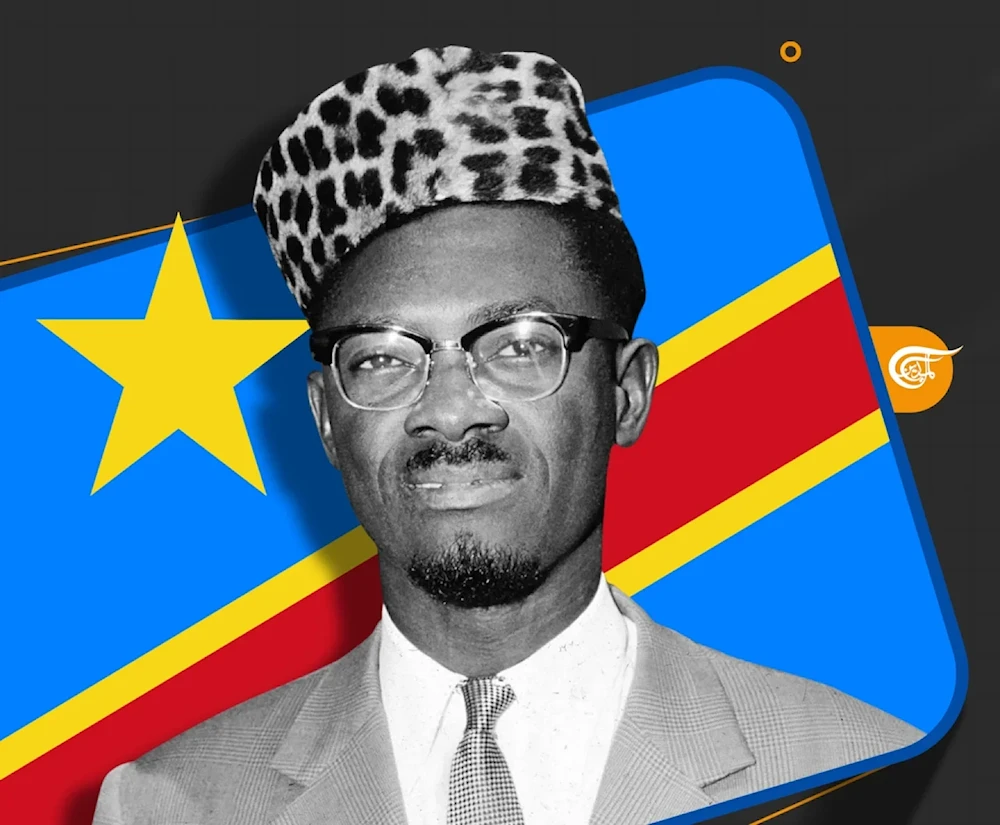

Patrice Lumumba: The national hero of the DR Congo

Patrice Lumumba served as an exceptional leader in the history of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, standing as a national hero who put his life on the line for the struggle of liberation.

-

Patrice Lumumba: The national hero of the DR Congo

Patrice Lumumba was born on July 2, 1925, in Onalua, in the Katako-Kombe region of the modern-day Democratic Republic of the Congo. He attended a Catholic mission school, followed by a Protestant one. Over the years, he worked for a mining company, as a journalist, and later as a clerk at a postal office. He married Pauline Opango, and together they had six children. Following his assassination, his family was granted refuge in Egypt, being taken in by President Gamal Abdel Nasser and living under his auspices.

A glimpse into Congo

On August 1, 1885, the Congo was declared the personal possession of King Leopold II of Belgium. For 23 years, the Congolese people endured unspeakable brutality and atrocities under the Belgian crown, particularly those forced to work in the mines. In 1908, the Congo formally became a colony of the Belgian state.

Historians estimate that between 1880 and 1926, a combination of colonial atrocities and disease wiped out nearly half the Congolese population. Some scholars refer to this period as a “forgotten holocaust.”

By the late 1940s and throughout the 1950s, two major political currents emerged in the Belgian Congo, particularly in the capital, Léopoldville, demanding independence:

- One current called for a federal form of independence. It established the Association Bakongo pour l'unification, la conservation et le développement de la langue Kongo (ABAKO) in 1949, which Joseph Kasa-Vubu would later lead from 1954.

- The other sought full independence under a unified Congolese state. Its leaders were inspired by Belgium’s proposed “Thirty-Year Plan for African Emancipation,” a vision of gradual independence. Patrice Lumumba emerged as a key figure in this camp.

On October 5, 1958, Lumumba founded the Mouvement National Congolais (MNC) in Léopoldville, alongside Gaston Diomi Ndongala, Joseph Iléo, and others. In December of that year, he attended the All-African Peoples’ Conference in Accra, Ghana, which constituted a political turning point for the key revolutionary figure. There, he fully embraced the call for immediate independence and African unity, convinced that only a united continent could overcome the shackles of colonialism and underdevelopment.

At the conference, Lumumba found common cause with other revolutionary thinkers, such as Frantz Fanon, Kwame Nkrumah, and Félix-Roland Moumié. They believed that tribalism and ethnic divisions undermined national unity and served as tools for continued colonial dominance. By the end of the conference, Lumumba was appointed a permanent member of its Coordinating Committee.

In January 1959, the dissolution of ABAKO and the deportation of its leader, Joseph Kasa-Vubu, to Belgium triggered widespread violence, leaving hundreds dead. That October, the colonial gendarmes opened fire on a National Congress rally in Stanleyville, killing 30 and wounding hundreds. Lumumba was arrested and sentenced to six months in prison, sparking demonstrations and riots calling for his release.

Seizing on his absence, Belgian authorities convened a meeting in Brussels with Congolese independence leaders. Yet the delegates unanimously refused to attend without Lumumba present. Under pressure, the authorities released him on January 26, 1960, so he could join the talks. These negotiations resulted in an agreement to grant the Congo independence on June 30, 1960. On May 19, the new Basic Law, effectively the country’s constitution, was issued, establishing a centralized Congolese state.

Parliamentary elections were held in May. Based on the outcome, it was agreed that Joseph Kasa-Vubu would become president of the Congo, while Patrice Lumumba would serve as prime minister. On the agreed-upon date, King Baudouin of Belgium formally declared the Congo’s independence.

Lumumba confronts Belgium, the secessionists

On June 30, 1960, King Baudouin of Belgium and his prime minister attended the official ceremony marking Congo’s independence. The King’s speech provoked widespread outrage among the Congolese when he praised King Leopold II for his "genius" and "courage", hailing his actions as a “great achievement” that Belgium had steadfastly carried forward for 80 years. He spoke of how Belgium had sent its finest sons to Congo, first to rid the Congo Basin of the slave trade, then to unite the Congolese people into "one of Africa’s greatest independent nations," and finally to promote a happier life for the people across its provinces. He concluded by declaring that Leopold II “did not present himself to the Congolese as a conqueror, but as a civilizer.”

Lumumba responded with a thunderous and defiant address. "No Congolese will ever forget that independence was won in struggle, a persevering and inspired struggle carried on from day to day, a struggle in which we were undaunted by privation or suffering and stinted neither strength nor blood [...] That was our lot for the eighty years of colonial rule, and our wounds are too fresh and much too painful to be forgotten. We have experienced forced labour in exchange for pay that did not allow us to satisfy our hunger, to clothe ourselves, to have decent lodgings, or to bring up our children as dearly loved ones."

He went on: "Morning, noon and night we were subjected to jeers, insults and blows because we were "Negroes" [...] We have seen our lands seized in the name of ostensibly just laws, which gave recognition only to the right of might [...] We have experienced the atrocious sufferings, being persecuted for political convictions and religious beliefs, and exiled from our native land: our lot was worse than death itself."

"Who will ever forget the shootings which killed so many of our brothers, or the cells into which were mercilessly thrown those who no longer wished to submit to the regime of injustice, oppression, and exploitation used by the colonialists as a tool of their domination?" he defiantly said.

Lumumba’s speech electrified the Congolese public. It sparked mutinies in military barracks still under the command of Belgian officers and led to riots, particularly in the capital, Léopoldville, where European residents and foreign companies were targeted. Seizing the moment, Lumumba expelled the Belgian officers from the army. In retaliation, Belgium deployed troops to Léopoldville under the pretext of protecting its citizens.

The ties between Lumumba and Belgium frayed, and the final thread snapped. Harold Charles d'Aspremont Lynden, Belgium’s last Minister of African Affairs (1960-1961), wrote in a letter to King Baudouin dated October 5, 1960: “The principal objective that must now be pursued, for the good of Congo, Katanga, and Belgium, is the definitive elimination of Lumumba.”

Just days after independence, Moïse Kapenda Tshombe, with Belgian support, declared the secession of the Katanga province on July 11, 1960. Belgium quickly airlifted 9,000 troops into Congo over the span of ten days, aided by NATO under the guise of protecting Katanga. On August 12, Belgium inked an agreement with Tshombe recognizing Katanga’s independence. Lumumba held Belgium directly responsible for the secession and swiftly severed diplomatic ties.

Two weeks after Katanga's secession, Albert Kalonji declared the independence of Kasai province. The leaders of the Katanga and Kasai secessionist movements announced plans to form a union between the two regions and began working together to bring down Lumumba, backed by Belgian mining companies operating in Congo. In response, Lumumba ordered the Congolese army to reclaim the region and appealed to the United Nations for support. On July 14, 1960, the UN General Assembly approved a resolution authorizing military intervention by UN peacekeepers in Lumumba’s favor and ordered Belgium to withdraw its troops. However, the UN soon reversed its position, imposing a ceasefire that prevented Congolese forces from entering Katanga.

After the UN turned against him, Lumumba remained resolute in his resistance to the horrid imperialist ambitions in Congo. On September 2, 1960, he called for African solidarity and requested support from the Soviet Union to help counter Katanga’s secession. This alarmed the United States, which resolved to eliminate him. A cable dated August 26, 1960, sent by CIA Director Allen Dulles to agency operatives in Léopoldville, confirmed this. In it, Dulles wrote that the United States had decided to remove Lumumba. "His removal must be an urgent and prime objective and that under existing conditions this should be a high priority of our covert action," the cable read.

The coup and Lumumba’s murder

On September 4, 1960, President Joseph Kasa-Vubu, in utter violation of the constitution, issued a decree dismissing Lumumba and his government, and appointed a caretaker cabinet led by Joseph Iléo. Lumumba rejected the move and accused the president of treason.

Chief of Staff Colonel Mobutu Sese Seko exploited the power struggle between Kasa-Vubu and Lumumba to stage a military coup on October 10, 1960, with backing from the United Nations and the colonial powers.

Mobutu ruled for three months before handing power back to Kasa-Vubu, who formed a new government under Cyrille Adoula. Meanwhile, Lumumba, whom Mobutu accused of communist sympathies, was placed under house arrest along with several of his ministers.

On November 27, 1960, Lumumba attempted to flee to Stanleyville but was captured and returned to Léopoldville. He was transferred to the Hardy military camp in Thysville. On January 17, 1961, he was flown, alongside Maurice Mpolo and Joseph Okito, to Élisabethville in Katanga. There, they were brutally tortured by Katangese officials, including Moïse Tshombe, and by Belgian officers. That evening, all three men were executed and had their bodies dissolved in acid. The following day, many of Lumumba’s supporters were also executed, with the participation of Belgian soldiers and foreign mercenaries.

In the aftermath, a peasant uprising broke out, led by former education minister Pierre Mulele. His forces seized control of several areas in Congo, but Mobutu’s army, backed by Belgium and South African mercenaries, eventually crushed the rebellion.

On September 18, 1961, United Nations Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld of Sweden was killed when his plane crashed during a peace mission in Congo. Hammarskjöld had been a firm supporter of decolonization in Congo and notably responded to Lumumba’s plea for help by dispatching UN peacekeepers to contain the rebellion. His stance lends credence to the theory that his Congo policy angered the Americans, British, and Belgians, and may have contributed to his untimely death.

In 1962, government forces led by Mobutu, in coordination with UN troops, launched a campaign to retake the secessionist provinces of Katanga (renamed Shaba in 1971) and South Kasai. By January 1963, Katanga’s secession had come to an end.

Rehabilitating Lumumba’s legacy

A Belgian federal prosecutor conducted an investigation into the death of Patrice Lumumba, and in 2001 released a detailed report concluding that the order to assassinate Lumumba came directly from Moïse Tshombe and his government. The report also highlighted the significant involvement of the Belgian government, which had supported Katanga’s secession and whose officers took part in Lumumba’s execution. It further documented how King Baudouin had personally intervened with US President John F. Kennedy to prevent Lumumba's release.

In 2002, the Belgian government formally acknowledged its moral responsibility for the events that led to Lumumba’s death, expressing regret and offering an apology to his family and the Congolese people for the pain inflicted upon them.

In 2016, a single tooth, believed to be all that remained of Patrice Lumumba, was discovered and enshrined in a specially constructed mausoleum in the DRC capital of Kinshasa.

11 Min Read

11 Min Read