Khorasan: The Eternal Battlefield... and the Bleeding Heart of Asia - Chapter 3

This region has always witnessed upheavals and radical changes to this day, interposed with sometimes shorter, sometimes longer periods of calm.

-

Chapter 3

The Persistence of the Persian Language...

The upheavals and radical changes in this region continue to this day, interposed with sometimes shorter, sometimes longer periods of calm. Despite all the invasions, wars, destruction, and eras of foreign rule, the spirit of ancient Iranian culture has always managed to survive in Khorasan, rising again and again like a phoenix from the ashes in the body of the "Dari-Persian" language.

All foreign and local rulers of other cultural origins and mother tongues left Dari Persian untouched in their domain as the official language – a kind of "lingua franca" – and also for their literature. Some of these foreign ruling dynasties made names for themselves by promoting and disseminating the literature of the time in Dari-Persian.

The Sassanid King Bahram Gor (421-438 AD), in whose home province of Pars the Middle Persian language (known as "Pahlavi Persian") was widely spoken, elevated Dari Persian – which had in fact evolved from Middle Persian in Khorasan – to the status of the court language and the official language of the whole of Sassanid Empire.

Only two ruling systems attempted to eradicate Dari Persian from the region: the Arab Caliphate, when it occupied Greater Iran (including Khorasan) in the 7th and 8th centuries... and the Pashtun state, since the beginning of the 20th century in what is now "Afghanistan".

This assault on the Dari-Persian language now remains ongoing.

After the fall of the Sassanids in the 7th century, Arab armies conquered and occupied western Iran. The Arabs subsequently introduced a new administrative system modelled on that of the Sassanids, and, initially, everything written by the administrative authorities was in the Persian language...

But the Umayyad ruler Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan decided to change the language in the Divan (the administration) from Persian to Arabic. This marked the beginning of the "Arabisation" of the conquered territories. The Umayyads, for all intents and purposes, practised a chauvinist to racist apartheid policy in all societal spheres against the defeated Iranian peoples. The use of the Persian language was penalised, and Arabic was deemed the sole official language. From then on, all matters in administration, science, literature, and other fields involving correspondence were to be conducted solely in Arabic; violators were to be punished. Nevertheless, the population persisted in speaking Persian at home... on the streets... and in the markets. This repression of the Persian language ultimately led to mounting insurrections and revolts.

It was the uprising conducted by Behzadan Pure Wandad Hormozd, better known as Abu Moslem Khorassani, that eventually brought about the overthrow of the Umayyads and the founding of the Abbasid Dynasty by Abu Moslem himself (in 750 AD).

The imperial capital was moved from Damascus to Baghdad. The Umayyads belonged to the aristocratic class of Makka (Mecca), whose rule was known as the "Arab Caliphate"; while that of the Abbasids was called the "Islamic Caliphate".

But it was not long before other Iranian peoples rose up against the Abbasids and established their own states. The Tahirids were the first dynasty to declare autonomy and establish their own state in Khorasan. During their rule, the Persian language was gradually revived in the literary fields.

Yaqub Layth Saffar, the founder of the Saffarid Dynasty (861-1003), ultimately abolished the use of Arabic in literature and in the administration by banning the language throughout his empire. Nevertheless, Arabic continued to be employed in scientific fields for some time.

It was under the Samanids (819-1005) and the Ghaznavids (997-1186 – in fact a dynasty of Turkic origin), that Dari Persian reached its golden age.

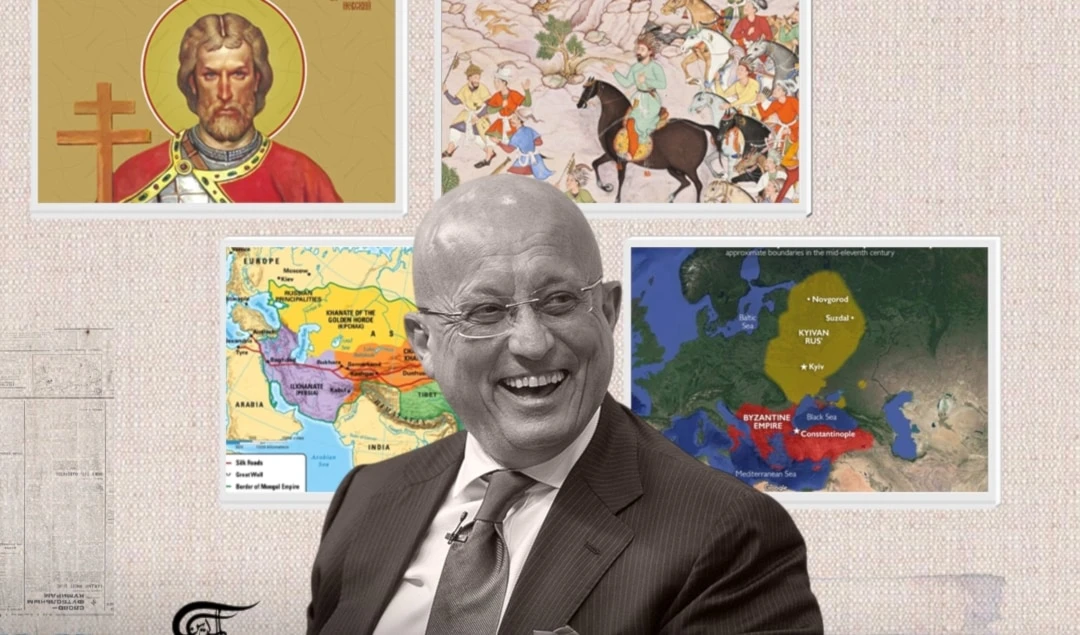

The region in which Persian was used as the lingua franca and as an official and cultural language extended as far as India (thanks to the Mongols who brought it there) and to Northwest China, as well as into the Caucasus, Asia Minor, and the Balkans.

-

The spread of the Persian language

For centuries, Khorasan sustained the rule of Greeks, Hindus, Arabs, Turks, Mongols, and Uzbeks...

For the inhabitants of Khorasan, the question of whether the ruling dynasty, government, or state consisted of their own people or of foreigners never played a crucial role as has often been claimed. Indeed, in this region, the ruling dynasties often did not hail from the local population. As long as these rulers vouchsafed, supported, or went so far as to even promote the Persian language and culture and guaranteed social and inter-ethnic justice, they were accepted. But as soon as these criteria were violated, popular resistance would break out, which, depending on the circumstances, would also lead to full-scale combat.

All the conquerors never had a "plan B" for the time after their conquests... In order to maintain and administrate Khorasan, they were obliged to rely on local populations and their elites – Persian-speaking Iranians... and it was not long before the Khorasan people became the veritable administrators and, as is often the case, the veritable "rulers" of the empire.

Following the Timurid Empire (1370-1506), Khorasan gradually lapsed into cultural decline and poor governance, circumstances that only worsened during the Safavid Era and scarcely improved under the two hundred years of Pashtun rule until today.

Over the centuries, Khorasan experienced a great variety of religions; polytheism, Mithraism, Zoroastrianism, Zurvanism, Manichaeism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Islam...

Western Iran (today's Islamic Republic of Iran) was conquered and Islamised relatively quickly by the Arabs, while large parts of eastern Iran (Khorasan) resisted Islam for centuries. The last non-Muslims in the region, the Kalash, who were called "Kafaran" or "Kafirs" (infidels) by others, were only "converted" to Islam in the 19th century by the despot Amir Abdoll Rahman, and their land "Kafaristan" ("land of the infidels") was renamed "Nurestan" ("land of light"). Like the Pashtuns, the majority today are devout Muslims. But a minor section of their population (now in Pakistani territory) still retain their animistic beliefs.

Of all these religions, Islam remains the most widespread and enduring today. (There are, of course, reasons and factors for this, but that is a topic for another essay.)

Religion and faith have always played an important role in Khorasan. But the people always gravitated more to a universal spirituality rather than to a dogmatic, fundamentalist version of Islamic religion and ideology (as an organised, fixed, limited system).

Thus, the people of Khorasan, regardless of their ethnic and linguistic affiliation, may have converted to Islam, but in doing so they retained aspects or important elements of their earlier beliefs and traditions... And in order for these "vestiges" to remain viable, they were gently tinged or vigorously blended with the prevailing "hues" of Islam. To cite an example... in the northern part of Khorasan, south of the Oxus, lies the town of Mazare Sharif in the Balkh province, home to the Blue Mosque (also known as Mazare Hazrat Ali - the "Tomb of Hazrat Ali"). Here, every year on the 1st of Farwardin (the first month of the Solar Hijri calendar which corresponds to the 21st of March), the "pagan" New Year – Nauroz is celebrated with a special, unique ceremony. (In the 1990s this celebration was banned for years by the Taleban; how the new Taleban administration – if they are still in power – will respond to the coming Nauroz festivities remains to be seen.) The exceptional observance of Nauroz at this particular site led some historians to speculate on a concrete affiliation between the Blue Mosque and ancient Zoroastrian fire temples. Though such a speculation could not be confirmed, it remains a clear example of pre-Islamic Iranian traditions living on in Islamic garb.

Spiritualism, which has its roots in pre-Islamic religions and cultures, gave rise to numerous mystical Sufi schools, orders, and sects over time.

Islamic Sufism and mysticism (Tasawwuf/Erfân – mysticism/Sufism) in Iran is an amalgamation of Islam with Iranian pre-Islamic faiths comprised of the Zoroastrian religion, Mithraism, Zurvanism, Manichaeism... with elements of Hinduism, Buddhism, Greek mysticism and philosophy (especially stoicism, Neoplatonism) and Christian Nestorianism.

Some scholars, such as Edward G. Browne, argue that Sufism and mysticism in Iran was an "Iranian reaction to the dry orthodoxy of Semitic Islam". The following statement by Abu Sa'id Abu'l-Khayr, an eminent Sufi and mystic from Khorasan (10th century), seems to support that idea:

"Tasawwuf is like a mill that transforms the coarse into something fine."

Sufism and mysticism are, of course, not confined to the Iranian cultural sphere... They were established and developed throughout the Islamic world from their inception and still have their place in the Islamic world today - from India, China, and Indonesia to West Asia, Eastern Europe, Spain, North Africa, and East Africa...

But what gives these schools of thought a special status in Khorasan and western Iran, apart from their political role, is their inseparable connection with the Iranian-Persian language and culture, which remains at the core of the identity of the people in today's Iran and Khorasan. This is also the reason why the Persian language and its associated traditions were so important to the Persian-speaking people of ancient Khorasan and remain so for them in Afghanistan today.

This identity has been under attack in Afghanistan for a hundred years.

Tariq Marzbaan

Tariq Marzbaan

9 Min Read

9 Min Read