No, China is not a threat in the EV sector

Chinese EV brands help diversify choices in markets open to them, which is favorable for car buyers under any circumstances.

-

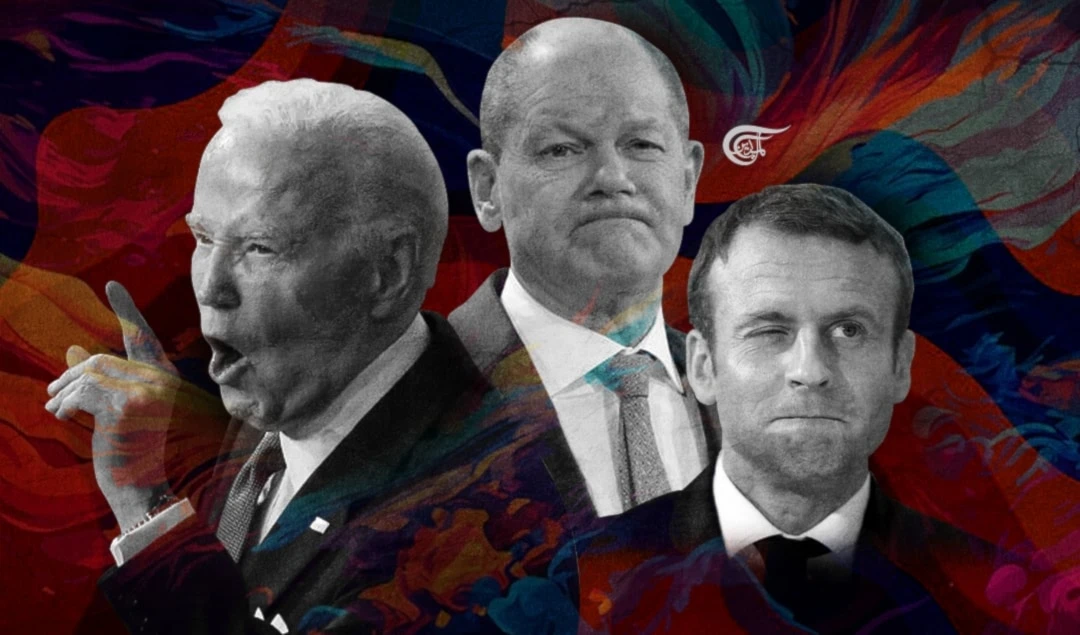

Illustrated by Zeinab El Hajj

Thanks to an industrial policy that has worked well, China’s electric vehicle industry is showing some signs of initial success. Moody’s predicted last month that China is on course to overtake Japan as the world’s top auto exporter by the end of 2023, largely due to the surging demand for China-made EVs. On another front, China currently claims over 70% of the global battery cell production capacity.

However, this momentum appears to be leading to a renewal of the “China threat” theory. A main theme of Western media’s coverage of the recent high-profile IAA auto show in Munich was how European auto giants were fighting to fend off Chinese challengers. A recent report by German insurer Allianz warned that Chinese-built battery EVs could cost European automakers billions of euros a year in lost profits by 2030. By the same token, investment bank UBS recently downgraded its rating on Volkswagen, saying it is the most exposed carmaker to the so-called threat from China. In the case of the US, no one needs a reminder about how the Inflation Reduction Act is seeking to exclude Chinese-made EVs from the American market.

Frankly, it is far from reality to describe the relations between Chinese EV makers and established Western auto brands as a zero-sum game. In many ways, further development of the EV sector requires deepened cooperation between the two groups.

The strategic partnership between Volkswagen and the Chinese brand XPeng represents a good case to look at. It was announced in July after the former invested $700 million into the latter. From Volkswagen’s perspective, access to XPeng’s EV and smart car technologies enables the German company to accelerate its electric transition. Meanwhile, XPeng has a lot to learn from Volkswagen’s auto expertise as well, and Volkswagen’s distribution network could be helpful to XPeng’s global expansion. XPeng is yet to make profit, so cash from Volkswagen can help sustain its R&D investment.

In other words, that is a complementary tie-up that could potentially set a precedent as to how Western automakers and Chinese EV brands could, in a win-win manner, tap into each other’s resources for the sake of future growth. Common sense tells us that Volkswagen would not have entered this deal had it seen Chinese EVs as a threat. Therefore, it’s probably not surprising that Volkswagen has shrugged off UBS’ rating downgrade.

For battery-powered EVs, the battery is the single most valuable part, and it can make up more than 40% of a vehicle’s cost. In fact, a report released in April by the European Automobile Manufacturers Association, a main auto lobby group in the EU, suggested that affordability concerns remained a significant obstacle for European consumers’ shift to purchasing EVs. Given the fact that the EU is the second largest EV market after China, affordability might be even a bigger concern in less advanced markets elsewhere. China’s leading position in EV batteries provides a solution to this issue.

Prices for cells are often more than a quarter lower in China than in Europe, according to a survey by London-based price reporting agency Benchmark Minerals. Since 2018, Chinese battery firms have announced investments in Europe worth more than $17 billion. By lowering the cost of batteries, such investments have benefited many EV manufacturers in Europe. Chinese market leader CATL’s existing battery plant in central Germany has been widely welcomed, and that’s why the company is working with Mercedes Benz in building another factory in Hungary that would be the largest of its kind in Europe. Professor Ferdinand Dudenhoeffer, Director of the Centre for Automotive Research at Germany’s University of Duisburg-Essen, has in a media interview called on German politicians to make sure that Chinese battery makers are not driven out of the country with what he considers as “stupid decoupling strategies.”

With regard to the US battery production, data compiled by Bloomberg show that China had a 24% cost advantage over the US last year. This prompted Ford to license technology from CATL as part of a plan to build a battery factory in Michigan. Compared to other options, CATL’s formula represents the cheaper and less energy-intensive one. Unfortunately, due to the anti-China sentiment in Washington, this partnership is facing a congressional probe, even though the planned factory would be fully owned by Ford. Amid US accusations against China over so-called “technology theft”, American lawmakers who initiated this investigation seem to have forgotten that, in this case, it is China that is sharing a more advanced technology with the US. Similar to the 5G case, some US carmakers’ electrification might need to bear a higher cost if US authorities seek technological decoupling from China in the EV sector.

In a bigger picture sense, regardless of whether Western automakers will stand to lose from the rise of Chinese EVs, we ought to look beyond corporate interests. Chinese EV brands help diversify choices in markets open to them, which is favorable for car buyers under any circumstances. A well-functioning market is supposed to offer as many choices as possible to its consumers. KPMG expects Chinese carmakers to capture some 15% of Europe's EV market by 2025. This forecast is of course based on European consumers’ growing recognition of Chinese EVs’ affordability and, possibly, quality. Apart from Western markets, consumers across the vast developing world also have a say. Let’s not forget that Saudi Arabia, Chile, and Mexico are currently the top three single-country destinations for China’s EV exports.

At the end of the day, embracing EVs is about pursuing green development. This is true for every country. China’s government figures indicate that all the EVs on the country’s roads can reduce a total of 15 million tonnes of carbon emissions on annual basis, the effect of which is, by some estimate, equivalent to planting over 2.9 billion trees. In the face of the climate crisis, working together is certainly more important than industrial rivalry. Each time officials from Washington urge China to do more on climate issues, any reminder of the US government’s actual attitude toward China’s EV industry might reinforce a sense of irony.

Ding Heng

Ding Heng

6 Min Read

6 Min Read