Lebanon’s invisible talent: The crisis of under-identifying gifted girls

In Lebanon, gifted girls are systematically under-identified despite outperforming boys academically, a loss of talent that the country can no longer afford, Dana Kahil argues.

-

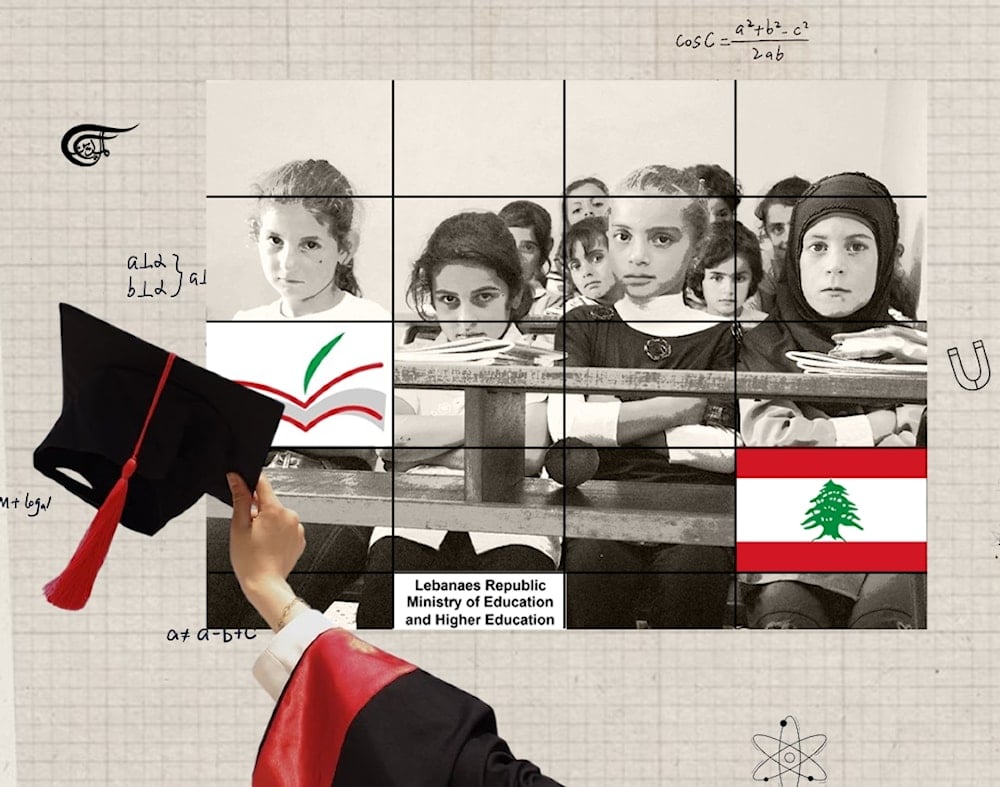

To secure Lebanon’s future, the brilliance of gifted girls must no longer remain invisible. These girls must be seen, nurtured, and empowered to shape the future of the country. (Al Mayadeen English; Illustrated by Batoul Chamas)

In Lebanon, girls consistently outperform boys in academic achievement, particularly in subjects such as language arts, reflecting a global trend. According to a meta-analysis by Voyer and Voyer (2014), girls outperform boys in scholastic achievement across the board, especially in reading and language arts, where they score, on average, 10-15% higher than their male counterparts. Despite this, Lebanese girls remain significantly underrepresented in gifted education programs, with national data indicating that only 29% of gifted students in Lebanon are girls (UNESCO, 2021). This systemic oversight is not only a loss for the individual girls but also represents a critical intellectual deficit for Lebanon at a time when national renewal is essential.

The discrepancy in the identification of gifted students is linked to deeply ingrained biases in the way giftedness is defined. Historically, giftedness has been associated with traits such as assertiveness, leadership, and intellectual risk-taking, qualities that are often more closely aligned with stereotypical male behaviors. According to Bianco et al. (2011), “teachers were significantly more likely to recommend boys over girls for gifted services even when academic achievement was identical” (p. 178). This bias occurs because educators tend to view giftedness through a narrow lens, focusing on observable behaviors like dominance and verbal assertiveness, which are culturally associated with male students. As a result, girls who may exhibit more internalized forms of giftedness, such as creativity, empathy, and emotional intelligence, are frequently overlooked.

This issue is particularly pronounced in Lebanon and other Middle Eastern societies, where cultural norms further contribute to the under-identification of gifted girls. Cultural expectations in these regions often emphasize modesty, compliance, and self-effacement, especially among girls. Ziegler and Stoeger (2017) note that these cultural norms discourage gifted girls from exhibiting behaviors that are often linked to leadership and assertiveness, traits mistakenly assumed to be indicators of giftedness. Al-Hroub (2010) emphasizes how societal pressures in Lebanon create environments where gifted girls are more likely to downplay their abilities, fearing they might be labeled as arrogant or "unfeminine." This pressure to conform prevents many gifted girls from being recognized for their intellectual capabilities, as they struggle to meet the traditional criteria for giftedness that are inherently biased toward behaviors typically seen in boys.

The cultural pressures on gifted girls in Lebanon are compounded by the educational system's reliance on standardized achievement tests and IQ scores, which further marginalize those whose talents manifest in non-traditional ways. Al-Hroub (2010) highlights that the Lebanese educational system predominantly identifies giftedness through these narrow metrics, which often fail to capture creative, emotional, or leadership abilities. As a result, girls who demonstrate exceptional skills in these areas are frequently left out of gifted education programs, despite excelling in other ways.

The psychological consequences of this systemic neglect are profound. Davis and Rimm (2004) provide a crucial perspective on the issue of underachievement among gifted girls. They explain that gifted girls often internalize societal pressures, leading to underachievement. These girls are socialized to seek approval and acceptance through compliance, rather than through independent thinking or leadership. As Davis and Rimm state, “The ideal of female behavior is often in direct conflict with the behavior necessary for success in gifted education programs” (p. 396). This conflict between societal expectations and the behaviors necessary for success in gifted programs creates a dissonance for many gifted girls, leaving them uncertain about whether they are “good enough” or worthy of recognition.

Rimm (2008) explains that many gifted girls “downplay their talents to fit into social expectations, sacrificing personal achievement for social acceptance” (p. 46). This internalized pressure leads to perfectionism and imposter syndrome, as gifted girls often feel as though they do not deserve their success or fear that their achievements will be dismissed or invalidated by others. This phenomenon, described by Reis and Hébert (2008), is a significant contributor to underachievement among gifted girls. They note that many gifted girls develop coping mechanisms that involve “masking their abilities, withdrawing from challenges, and lowering aspirations to avoid peer rejection” (p. 220). This behavior is a direct response to the cultural and educational pressures that require them to minimize their brilliance in order to fit into socially accepted molds of femininity.

The cost of this under-identification and the resulting disengagement is not only personal but societal. The failure to recognize and nurture the intellectual potential of gifted girls constitutes a profound loss for Lebanon, especially in a nation already grappling with economic instability and political turmoil. According to the World Economic Forum (2023), closing gender gaps in education and labor force participation could increase global GDP by $12 trillion by 2025. In Lebanon, failing to harness the intellectual potential of gifted girls could cost the nation as much as 2.5% of its GDP annually. The economic impact of underutilizing female intellectual capital is staggering, and it is clear that Lebanon cannot afford to overlook the talents of half of its population.

The solution to this crisis lies in the implementation of gender-fair identification tools that can capture the full range of giftedness among students, regardless of gender. Tools such as the Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking and the WISC-V can help identify talents that are often missed by traditional achievement tests (National Association for Gifted Children [NAGC], 2019). These tests can surface giftedness in areas such as creativity, emotional intelligence, and leadership, qualities that are often present in gifted girls but go unrecognized by traditional metrics.

Dweck (2006) underscores the importance of cultivating a growth mindset in gifted girls, teaching them that intelligence is not fixed but can grow with effort and persistence. This mindset shift is crucial, as it enables gifted girls to see themselves as “good enough” and helps to combat the self-doubt and perfectionism that often accompany underachievement. As Davis and Rimm (2004) note, a critical component of addressing the underachievement of gifted girls is helping them embrace their intellectual potential without fear of social rejection or failure. By encouraging girls to see their abilities as something to be proud of, rather than something to hide, Lebanon can help them realize their full potential and contribute to national development.

Moreover, teacher training is essential to addressing the under-identification of gifted girls. Currently, fewer than 30% of teachers in Lebanon receive formal training in identifying gifted students (Al-Hroub, 2010). Teachers must be educated to recognize giftedness in its various forms - creativity, leadership, emotional intelligence, and problem-solving abilities - and to value these traits as much as academic achievement. Educators need to understand that gifted girls may not always display the assertive behaviors that are traditionally associated with giftedness but may instead exhibit quieter forms of brilliance that still deserve recognition and support.

Visibility and mentorship are also key factors in addressing the under-identification of gifted girls. As Dr. Sally Reis (2002) emphasizes, gifted girls need role models and peer networks where their talents are celebrated rather than hidden. These safe spaces allow gifted girls to see other girls who share their intellectual drive and to understand that their ambition and brilliance are not only acceptable but essential. As Dr. Reis aptly states, "Gifted girls must be visible to each other. They need to know they’re not alone—and that their gifts matter" (p. 103). These safe, supportive environments give gifted girls the validation they need to continue striving for excellence without fear of rejection. As Davis and Rimm (2004) argue, girls need to see themselves as capable of success in gifted education programs and beyond. Without role models who embody this belief, many gifted girls will continue to doubt their worth and potential.

In a nation battling economic collapse, mass emigration, and social fragmentation, we cannot afford to let brilliance go unnoticed. We cannot afford to silence the voices of gifted girls whose innovations, empathy, and vision could help reshape the future. Talent is everywhere, as Dr. Rimm reminds us—but opportunity is not. It is time for Lebanon to create that opportunity. We must act. Not tomorrow. Today. Lebanon stands at a critical juncture. In a nation already facing significant challenges, from economic collapse to political instability, the country cannot afford to ignore the intellectual potential of its gifted girls. Wasting the talents of half the population is a luxury Lebanon can no longer afford. By ensuring that gifted girls are identified, nurtured, and empowered, Lebanon can tap into an underutilized source of talent that will drive its intellectual, economic, and cultural renewal.

To secure Lebanon’s future, the brilliance of gifted girls must no longer remain invisible. These girls must be seen, nurtured, and empowered to shape the future of the country. By doing so, Lebanon can cultivate a new generation of leaders, thinkers, and innovators who will contribute to the country’s prosperity and success on the global stage. It is time to recognize the immense potential of gifted girls and give them the opportunities they need to thrive.

References

Al-Hroub, A. (2010). Developing assessment profiles for mathematically gifted children with learning difficulties at three schools in England using a multiple-criteria approach (PhD thesis, University of Warwick).

Bianco, M., Harris, B., Garrison-Wade, D., & Leech, N. (2011). Gifted girls: The challenges of being gifted and female. Roeper Review, 33(3), 170–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/02783193.2011.580500

Davis, G. A., & Rimm, S. B. (2004). Education of the Gifted and Talented (5th ed.). Pearson Education.

Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

National Association for Gifted Children. (2019). Identifying and serving culturally and linguistically diverse gifted students. NAGC.

Reis, S. M. (2002). Developing academic talent in young women. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 13(4), 98–103. https://doi.org/10.4219/jsge-2002-365

Reis, S. M., & Hébert, T. P. (2008). Gender and giftedness. In S. I. Pfeiffer (Ed.), Handbook of giftedness in children (pp. 215–234). Springer.

Rimm, S. (2008). Underachievement syndrome: Causes and cures (3rd ed.). Great Potential Press.

UNESCO. (2021). Cracking the code: Girls’ and women’s education in STEM. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Voyer, D., & Voyer, S. D. (2014). Gender differences in scholastic achievement: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1174–1204. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036620

Dana Kahil

Dana Kahil

10 Min Read

10 Min Read