Reimagining English Literature instruction in Lebanese public schools: Critical gateway to intellectual, cultural development

By integrating literature into curricula, Lebanese public schools can nurture vibrant intellectual communities where students learn not only from texts but also from each other.

-

Literature fosters analytical thinking, problem-solving, and interpretive fluency (Illustrated by Mahdi Rtail for Al Mayadeen English)

In a world increasingly defined by the fluid movement of people, ideas, and information across national and cultural boundaries, language instruction must be reimagined not simply as a means of achieving functional literacy or communication skills but as a critical gateway to global culture, intellectual engagement, and civic readiness. Lebanon’s rich multilingualism is an essential part of its national identity, reflected in an educational system where Arabic, French, and English coexist. English, in particular, holds a long-standing presence in both private and public school curricula. Yet, in Lebanese public schools, English education remains narrowly utilitarian, focused mainly on grammar, vocabulary, basic conversational proficiency, and occasional translation exercises. English literature, the rich body of texts that can cultivate critical thinking, cultural empathy, and intellectual depth, is largely absent from public school curricula. This exclusion is not merely a curricular oversight but a lost opportunity to cultivate critical intellectual skills and intercultural awareness among Lebanon’s youth.

Moreover, literature’s capacity to present realistic, multidimensional characters plays a crucial role in student engagement and identity formation. When students encounter characters grappling with complex emotions, moral dilemmas, and social challenges, they see reflections of their own experiences and those of others, enabling a deeper connection to the material. This identification fosters empathy and self-awareness, as students begin to understand that their struggles and triumphs resonate within a larger human context. In formal classroom settings, characters such as Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Achebe’s Okonkwo, or Darwish’s poetic personas become living catalysts for dialogue, inviting students to explore motivations, conflicts, and consequences in ways that abstract facts alone cannot inspire. These narratives serve as safe spaces for students to explore identity, ethics, and social realities, facilitating personal growth alongside academic development (Rosenblatt, 1995). The ability to relate to such characters helps students develop critical emotional intelligence and moral reasoning, skills vital to their holistic education.

In addition to fostering individual identification, literature naturally elicits interactive discussions that enhance learning outcomes in both formal and informal educational contexts. Classroom discussions centered on literary texts promote active engagement, encouraging students to articulate their interpretations, challenge assumptions, and consider diverse perspectives. Such dialogues foster collaborative learning and critical discourse skills essential for academic success and democratic participation (Applebee, Langer, Nystrand, & Gamoran, 2003). Informal discussions, whether among peers outside the classroom or within community settings, extend the reach of literature’s impact, promoting cultural exchange and reinforcing interpretive skills in naturalistic environments. This dialogic process enables students to negotiate meaning collectively, developing communication skills and social awareness. By integrating literature into curricula, Lebanese public schools can nurture vibrant intellectual communities where students learn not only from texts but also from each other, preparing them to participate thoughtfully in Lebanon’s pluralistic society and the broader global community.

Reducing literature to a mere tool for language acquisition fundamentally undervalues its deeper educational function. Literature invites students to engage with complexity, ambiguity, and the rich textures of human experience and history. For example, George Orwell’s Animal Farm offers more than an introduction to allegory; it provides a powerful lens for critically examining the corrupting effects of power and the cyclical failures of revolutionary movements. Through such texts, students do not passively absorb information but actively interpret and analyze, engaging in a form of critical pedagogy that enhances reasoning and reflection. Critical pedagogy empowers learners to question dominant narratives and to develop intellectual autonomy (Facione, 2011; Paul & Elder, 2014).

Empirical research supports the cognitive benefits of literature-centered education. A meta-analysis of instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills by Abrami et al. (2008) demonstrated a statistically significant improvement in reasoning abilities when critical-thinking strategies were integrated into curricula. These findings reflect a broader educational consensus that literature fosters analytical thinking, problem-solving, and interpretive fluency, skills that transcend language learning and enhance intellectual engagement. Furthermore, education that promotes critical literacy can reduce susceptibility to misinformation and cognitive biases, underscoring the role of literature and the humanities in cultivating intellectual resilience (Pennycook & Rand, 2019).

Beyond cognitive development, literature functions as a powerful bridge across cultural boundaries. Exposure to diverse literary voices expands students’ understanding of other cultures and historical experiences, enriching rather than diluting national identity. Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart introduces readers to the psychological and cultural trauma of colonialism through the character of Okonkwo, transforming abstract historical realities into accessible lived experiences (Achebe, 1958). Likewise, Emily Dickinson’s poetry invites introspection and emotional resilience, encouraging students to engage with complex inner states (Vendler, 2010). These encounters cultivate empathy and cultural literacy, essential competencies in a globally interconnected world.

Scientific studies corroborate literature’s unique ability to enhance empathy and social cognition. Kidd and Castano’s (2013) five experiments with over one thousand participants showed that reading literary fiction causally improves theory of mind, the capacity to understand others’ emotions and mental states. Mar et al. (2011) further demonstrated that immersion in fictional narratives leads to sustained increases in empathy, provided readers emotionally engage with the texts, with a beta coefficient of 0.17 and a p-value less than .05. These findings underscore literature’s role in fostering emotional intelligence and intercultural sensitivity, competencies vital for social cohesion and civic participation.

Despite this evidence, Lebanese public schools largely exclude English literature from their curricula, while private institutions often provide access to such enriching instruction. This divide perpetuates inequities not only in socio-economic terms but in intellectual and civic development. Private school students cultivate critical thinking, cultural literacy, and interpretive skills that better prepare them for university education and global engagement, whereas public school students remain limited by a narrow focus on functional English (Harb & Saab, 2014).

This disparity undermines education’s broader mission, which must go beyond rote learning and examination preparation to nurture thoughtful, engaged citizens. Literature equips students to become critical thinkers, able to analyze texts, question dominant discourses, and appreciate cultural complexity. Such skills are essential for navigating the complexities of university education and for active participation in a democratic society (Nussbaum, 2010).

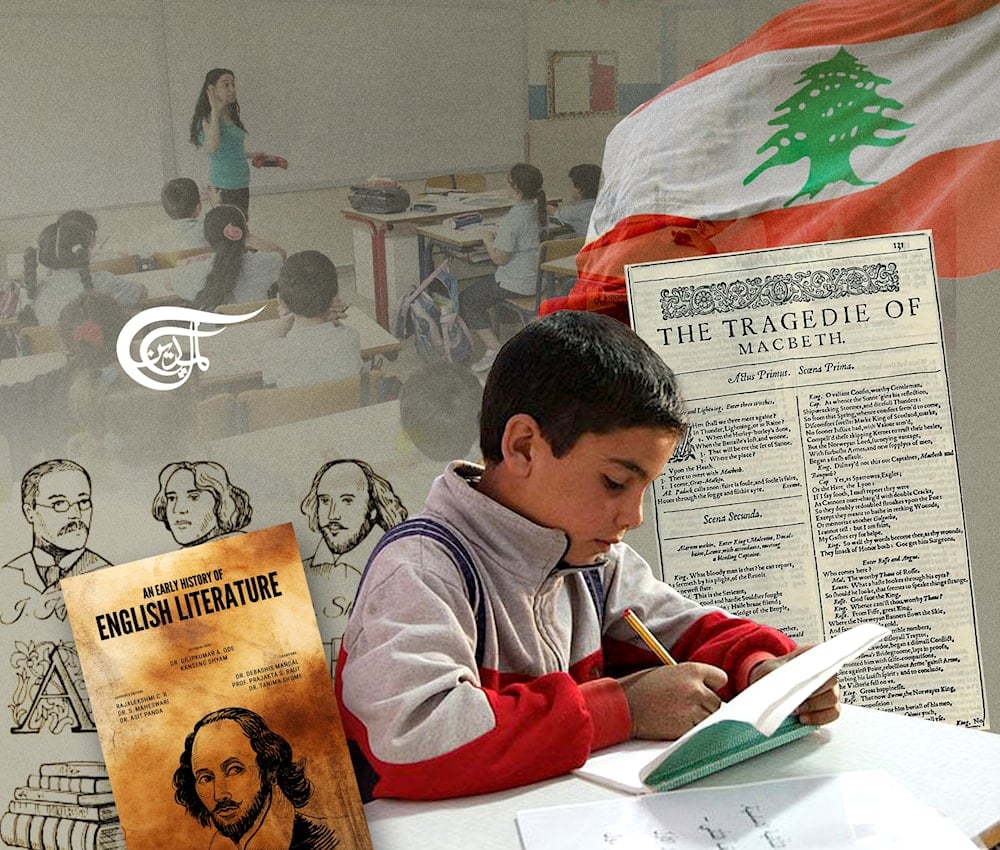

Therefore, this appeal is respectfully addressed to Her Excellency Professor Rima Karami, Minister of Education and Higher Education of Lebanon. We urge your esteemed office to lead a timely and visionary revision of the public-school curriculum to formally integrate English literature alongside Arabic literature as a core component of language education. This reform would not diminish the primacy of Arabic or French literary traditions but rather foster a multilingual literary consciousness that reflects Lebanon’s rich cultural heritage and its future aspirations. Introducing canonical works such as Shakespeare’s Macbeth alongside Arabic poets like Al-Mutanabbi and Mahmoud Darwish would create a powerful dialogic framework, promoting comparative literary analysis and critical thinking. This integration would enable students to explore universal themes such as ambition, identity, and morality through diverse cultural lenses, cultivating intellectual depth and cultural empathy (Said, 1993; Cummins, 2000).

Importantly, integrating English literature is not merely curricular expansion but a deliberate extension of literacy into the realm of humanism and civic education. Literature cultivates empathy, intellectual humility, and critical reasoning, qualities empirically linked to resistance to cognitive biases, misinformation, and cultural insularity (Pennycook & Rand, 2019). In an era marked by rapid globalization and social fragmentation, these qualities are indispensable for nurturing socially responsible citizens equipped to engage thoughtfully and respectfully in a pluralistic society.

Her Excellency, your leadership in addressing this curricular gap with foresight and commitment will democratize access to the cognitive and emotional benefits of literary education and empower Lebanese youth to participate actively and thoughtfully in global discourse. Such reform will affirm Lebanon’s identity as a crossroads of cultures and ideas, embracing multilingualism as a source of intellectual and moral strength. We trust that your vision will champion this essential evolution in Lebanon’s public education system for the benefit of current and future generations.

Ultimately, Lebanon’s educational future depends on equipping its youth not only with functional language skills but with the critical, cultural, and empathetic capacities necessary for global citizenship. English literature, with its unique capacity to foster critical thinking and intercultural understanding, must be integrated into the public-school curriculum alongside Arabic literature. Let English literature enter the classroom not as a foreign intruder, but as a vital companion to learning, a bearer of voices that echo across borders, and a guide to the minds and hearts of others. Let public school students be given the chance to read, to analyze, to imagine, and above all, to grow. This integration will help bridge intellectual and cultural divides and prepare a generation ready to navigate complexity, engage with diversity, and contribute meaningfully to the national and global community.

References:

Achebe, C. (1958). Things fall apart. Heinemann.

Applebee, A. N., Langer, J. A., Nystrand, M., & Gamoran, A. (2003). Discussion-based approaches to developing understanding: Classroom instruction and student performance in middle and high school English. American Educational Research Journal, 40(3), 685–730. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312040003685

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M., Tamim, R., & Zhang, D. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 1102–1134. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308326084

Cummins, J. (2000). Language, power and pedagogy: Bilingual children in the crossfire. Multilingual Matters.

Facione, P. A. (2011). Critical thinking: What it is and why it counts. Insight Assessment. https://www.insightassessment.com

Harb, C., & Saab, H. (2014). English in Lebanon: Its socio-political history and present dilemmas. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 17(6), 690–704. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2013.777783

Kidd, D. C., & Castano, E. (2013). Reading literary fiction improves theory of mind. Science, 342(6156), 377–380. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1239918

Mar, R. A., Oatley, K., Hirsh, J., Dela Paz, J., & Peterson, J. B. (2011). Bookworms versus nerds: Exposure to fiction versus non-fiction, divergent associations with social ability, and the simulation of social experience. Journal of Research in Personality, 45(5), 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2011.04.011

Nussbaum, M. C. (2010). Not for profit: Why democracy needs the humanities. Princeton University Press.

Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2014). Critical thinking: Tools for taking charge of your learning and your life (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Pennycook, G., & Rand, D. G. (2019). Fighting misinformation on social media using crowdsourced judgments of news source quality. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 116(7), 2521–2526. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1806781116

Rosenblatt, L. M. (1995). Literature as exploration (5th ed.). Modern Language Association.

Said, E. W. (1993). Culture and imperialism. Vintage Books.

Vendler, H. (2010). Poems, poets, poetry: An introduction and anthology. Bedford/St. Martin's.

Dana Kahil

Dana Kahil

10 Min Read

10 Min Read