How the Portuguese far right is scapegoating Bangladeshi immigrants

Timo al-Farooq reveals how Portugal’s far right is exploiting Bangladeshi immigrants as scapegoats amid a broader surge in racism, xenophobia, and anti-immigrant policy. The once-welcoming nation is rapidly embracing hardline nationalism.

-

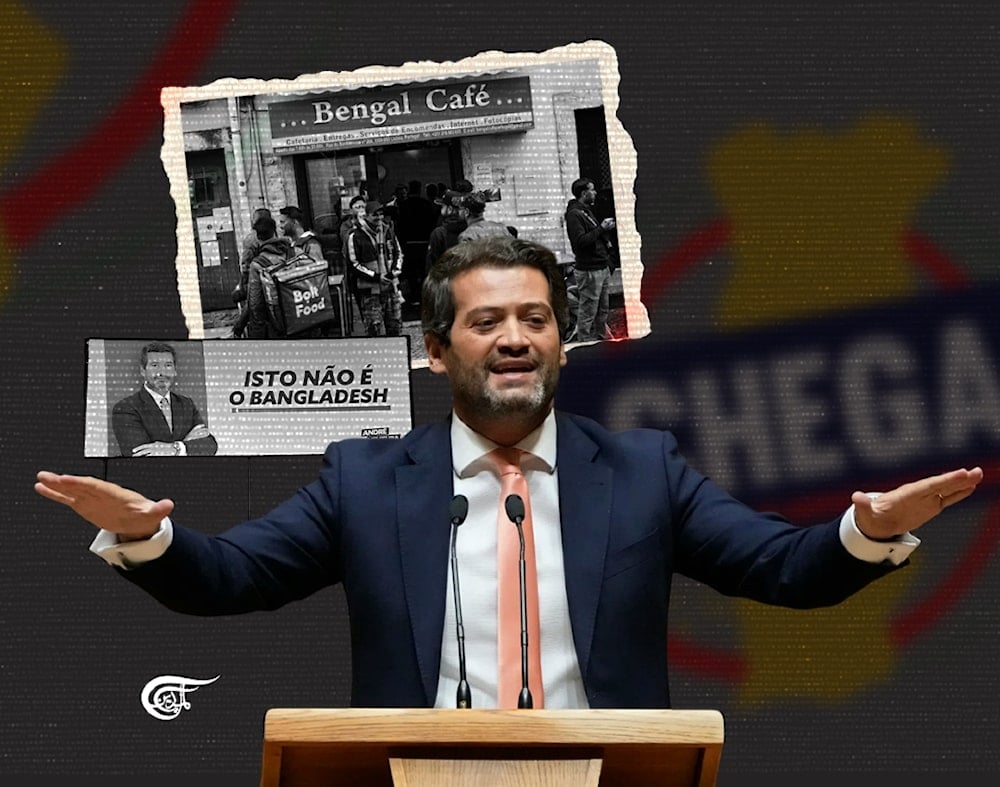

With CHEGA’s steady march to power and the increasing mainstreaming of racist rhetoric, behaviours and government policies, “visible minorities” are in for a rough time. (Al Mayadeen English; Illustrated by Batoul Chamas)

It is fascinating to see how the same immigrant community can be a kingmaker in one place and a punching bag in another.

While New York City’s Bangladeshi diaspora played a crucial role in Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral election victory, Bengalis on the other side of the Atlantic in Portugal are far from yielding that level of normalised, participatory power.

A racist campaign billboard featuring popular right-wing politician André Ventura is at the heart of a controversy over immigration to the EU nation, long seen as the last bastion of immunity to xenophobic populism in Europe.

The billboard features the leader of the far-right opposition CHEGA party, who is running in the upcoming presidential elections in January 2026, next to the slogan “Isto não é o Bangladesh” (This is not Bangladesh).

The crude dig at the estimated 50,000 members of Portugal’s Bangladeshi community is the latest expression of the far-right’s immigration-is-out-of-control hysteria and has triggered condemnations from anti-racism groups.

But Ventura, in keeping with his abrasive public persona, remained unapologetic and even doubled down.

“What is the problem with saying that Portugal is not Bangladesh? Do you want it to be? Would you like to live in a country like that? If that’s what you want, just catch a plane and don’t return. We will not let Portugal rot!” he ranted on X.

Lisbon’s Brick Lane

When traditional immigrant-receiving European nations began tightening immigration rules as a reaction to pressures from a growing far-right, Portugal quickly became a preferred destination for South Asian migrants due to its welcoming reputation and relatively speedy regularisation process.

I have met over-exploited Bangladeshi migrant labourers in Gulf states who were saving up their hard-earned wages to journey onwards to Portugal because it was (until recently) the quickest pathway to EU residency and citizenship.

In recent years, many Bangladeshis from wealthier European nations have also relocated to Portugal because of its more liberal residency requirements.

A Bangladeshi student I met in Berlin last year said he was moving to Portugal after having lived in Germany for eight years.

In that time, he told me, he had still not gained permanent residency and was not even allowed to sponsor his wife in Bangladesh to join him in Germany.

Portugal’s Bangladeshi diaspora is primarily concentrated in the capital Lisbon, with Rua Benformosa in the downtown Martim Moniz area constituting the heart of Bengali life in the country, a Portuguese version of London’s (pre-gentrified) Brick Lane.

One Bangladeshi shopkeeper there told me that he moved to Portugal after having lived in various other EU countries because it was “less racist” and the police did not harass you.

“Here you can live in peace”, he told me.

Homegrown woes

But that “peace” is seemingly coming to an end as an increasing number of Portuguese people are giving in to their smouldering nationalist urges by scapegoating immigrants for domestic problems, only half a century after the Carnation Revolution put an end to Europe’s longest-running fascist dictatorship and the Estado Novo’s bloody colonial wars.

In a desperate effort to appease disgruntled voters, who are flocking to CHEGA in droves, the centre-right coalition government has tightened residency and naturalisation rules and is cracking down on irregular migration in an unprecedented manner.

In May, the government announced its plans to begin expelling approximately 18,000 migrants. 9,268 departure notices were issued in the first half of this year alone, according to data released by the Agency for Integration, Migration and Asylum (AIMA).

The country that used to grant mass amnesty for undocumented migrants is now engaging in mass deportations.

Like other far-right parties across Europe, CHEGA has done a stellar job of blaming immigration for homegrown woes.

You will have a hard time convincing the average Ventura supporter that it is neoliberal government policies that are responsible for the exorbitant cost of living and housing crisis plaguing the urban centres of the country, not hardworking South Asian immigrants, many of whom live in cramped and dingy shared accommodations with wall-to-wall bunk beds crammed into them.

Residence-through-investment schemes such as the controversial Golden Visa have led to rapacious gentrification in cities like Lisbon where the hyper-commodification of the basic right of housing, embodied by for-profit behaviours such as house-flipping and mass-Airbnb-ing out flats to tourists and digital nomads, is severely limiting the availability of affordable rental units for low- and even middle-income citizens.

Portuguese racism

Ventura’s anti-Bangladeshi racism is embedded in the broader, nativist enmity towards anyone framed as “foreign.”

His presidential campaign billboards are also attacking Portugal’s Romani community, the most persecuted minority in Europe and a frequent target of Ventura’s race-baiting.

Roma associations have filed a criminal complaint over posters that read “Os ciganos têm de cumprir a lei” (Roma people must comply with the law).”

Despite their cultural links to Portugal, the 400,000 Brazilians living there are also not exempt from the country’s rising xenophobia.

In the last parliamentary election campaign, CHEGA’s anti-immigrant discourse accused them of exploiting the welfare system and contributing to a rise in crime.

With CHEGA’s steady march to power and the increasing mainstreaming of racist rhetoric, behaviours and government policies, “visible minorities” are in for a rough time.

Sadly, Portugal’s Bangladeshis are still a long way from possessing the political and discursive clout that their compatriots have in the UK, US or Canada and from being considered an integral part of Portuguese society.

The reaction of the Bangladeshi embassy in Lisbon to the billboards singling out its citizens for attack is indicative of this impuissance.

It put out a message in Bengali “asking all Bangladeshi expatriates to remain calm, sober and peaceful at all times. The appropriate authorities are being contacted by the embassy regarding this matter.”

As if Bangladeshis are the problem and not Portuguese racism.

Timo Al-Farooq

Timo Al-Farooq

6 Min Read

6 Min Read