Israeli bill uses archaeology as cover to usurp more Palestinian land

Critics warn “Israel” is weaponizing archaeology to entrench apartheid, shield settler violence, and tighten its grip on Palestinian land under the guise of preservation.

-

A Palestinian youth wears a traditional Palestinian dress during a show in the Palestinian Heritage day, at the historic archaeological center of the West Bank village of Sebastia, north of Nablus, Thursday, Oct. 7, 2021. (AP)

A proposed Israeli law to transfer responsibility for West Bank archaeological sites from the military Civil Administration to the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA) has sparked alarm among Israeli archaeologists, who warn it represents another step in “Israel’s de facto annexation of Palestinian land,” The Times of Israel reported.

What truly unsettles Israeli archaeologists is not the bill itself, but the potential loss of funding and the mounting global momentum of the BDS movement.

For centuries, the ruins of the Crusader-era fortress at Tal‘at ed Damm, or “Ascent of Blood”, a site recognized by the Palestinian National Authority as part of Palestinian territory, remained largely undisturbed.

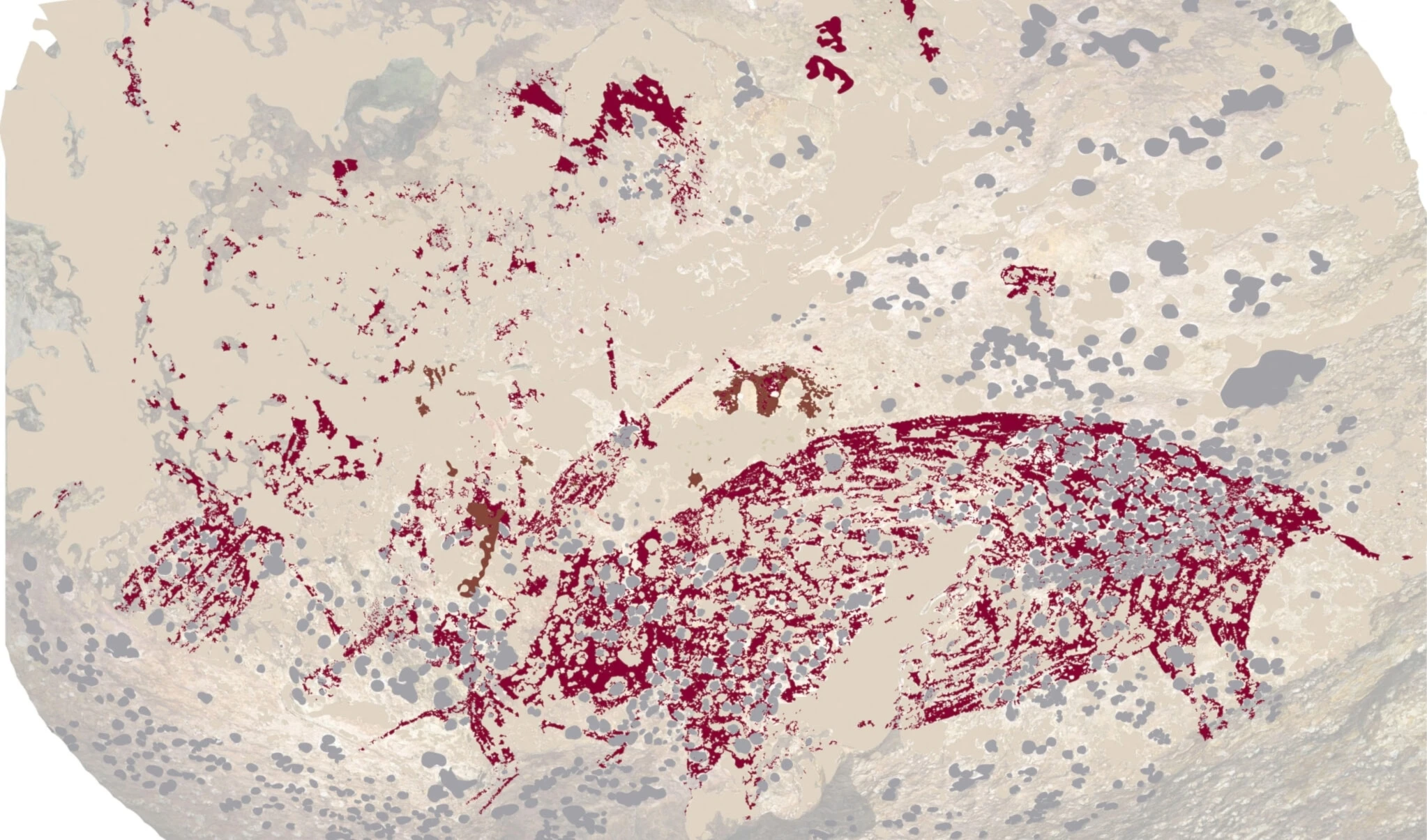

Recent excavations by “Israel’s” Security Ministry’s Civil Administration Archaeology Unit uncovered a Byzantine mosaic beneath Crusader remains, underscoring the depth of Palestine’s history. Unlike most digs overseen by the IAA, this project falls under the Civil Administration, which manages civilian affairs in the West Bank’s so-called Area C, according to the report.

Politicizing Archaeology

The occupied West Bank is home to some 2,600 archaeological sites spanning Christian, Muslim, and Jewish heritage. Under the Oslo Accords, “Israel’s” authority over antiquities is limited to the West Bank's so-called Area C, while the West Bank's so-called Areas A and B remain under the Palestinian Authority. Yet an Israeli bill from 2023 proposes transferring oversight from COGAT, the military liaison office, to the IAA, under the pretext of preservation. Critics told The Times of Israel the measure is a political maneuver designed to extend "Israeli civilian control" over occupied land.

Even the IAA has opposed the plan, warning it could damage international academic ties and undermine professional credibility. Experts also noted, as The Times of Israel reported, that replacing “military law” with “civilian law” in the West Bank would entrench "annexation" while weakening protections for archaeological sites.

Archaeological heritage in the occupied West Bank faces ongoing threats primarily from Israeli settler violence. Destruction has been documented at sites including the historic Church of St. George in Taybeh and the UNESCO-listed terraces of Battir, where settlers have repeatedly encroached.

Despite this, Israeli authorities rarely act against settler vandalism, reinforcing what critics told The Times of Israel is a system of selective enforcement designed to tighten occupation.

In Taybeh and across the occupied West Bank, settler violence often targets not only individuals but also livelihoods and agricultural land. Rights groups and religious leaders have documented repeated acts of sabotage, including settlers releasing livestock into Palestinian fields and town centers, destroying olive groves, and wrecking crops.

Taybeh’s landscape is deeply interwoven with Christian heritage, with its churches, shrines, and steeples rising over olive orchards. But this historic Christian community is under growing pressure. Since 1948, the Christian Palestinian population has dropped from about 10% to less than 1%, driven largely by forced emigration under the occupation.

International law and academic boycotts

Supporters of the bill, such as MK Orit Halevi, openly frame it as a step toward cementing “Israel’s sovereignty” over what "Israel" calls “Judea and Samaria.”

Opponents counter that the legislation has little to do with heritage preservation and everything to do with entrenching apartheid policies, legitimizing occupation, and normalizing settler control under the false guise of archaeology.

“The proposed law in its current form could cause great damage to the academic ties of the Israel Antiquities Authority and the State of Israel with international entities and damage their professional reputation,” an IAA spokesperson admitted to The Times of Israel.

Prof. Guy Stiebel of Tel Aviv University, chair of “Israel’s” Archaeology Council, which advises the government and public institutions, was even more direct, “I ask Halevi to be honest and just admit this is about sovereignty, in the small corner of archaeology.”

Others have been blunter in their criticism. “Israel and the settlers whom you have joined have weaponized archaeology in Jerusalem and the West Bank, using it as a lever to dispossess Palestinians,” charged Prof. Rafi Greenberg, chairman of Emek Shaveh, in an open letter to participants at the “Archaeology and Site Conservation of Judea and Samaria” conference in Jerusalem on February 13, 2025.

Alon Arad, executive director of Emek Shaveh, echoed that view, saying, “Israel cannot and should not use archaeology to justify acting against the Palestinians.”

The current situation underscores how archaeology in the West Bank has become a tool of “Israel’s” occupation. It is being weaponized in the Palestinian struggle over land, identity, and sovereignty under Israeli occupation.

For many critics, the drive to reshape archaeology is less about scholarship and preservation than about shielding Israeli institutions from academic boycotts, funding losses, and the growing global strength of the BDS movement.

5 Min Read

5 Min Read