How South Korean babies were falsely labelled orphans in a system of forced adoptions abroad

Leila Nezirevic uncovers how thousands of South Korean children were falsely labeled as “orphans” in a state-backed system of deception that trafficked them abroad under the guise of adoption.

-

Norway, long a major recipient of Korean adoptees, has faced repeated convictions in the European Court of Human Rights for violating basic rights in domestic adoption cases. (Al Mayadeen English; Illustrated by Batoul Chamas)

For decades, thousands of South Korean children sent abroad for adoption were told the same story: they had been abandoned, unwanted, or left behind by poverty. Adoption was presented as salvation, a rescue from hardship their families could not endure.

But today, an emerging body of evidence and testimony reveals a far darker reality: many of these children were never orphans at all. They were made into orphans—through a state-backed system that tore families apart and trafficked children abroad under false pretenses.

A childhood of emptiness

When Jung Kyung Sook was four, she remembers walking alone to kindergarten, watching other children grip their parents’ hands. The sting of loneliness followed her until a sudden fall left her bleeding.

-

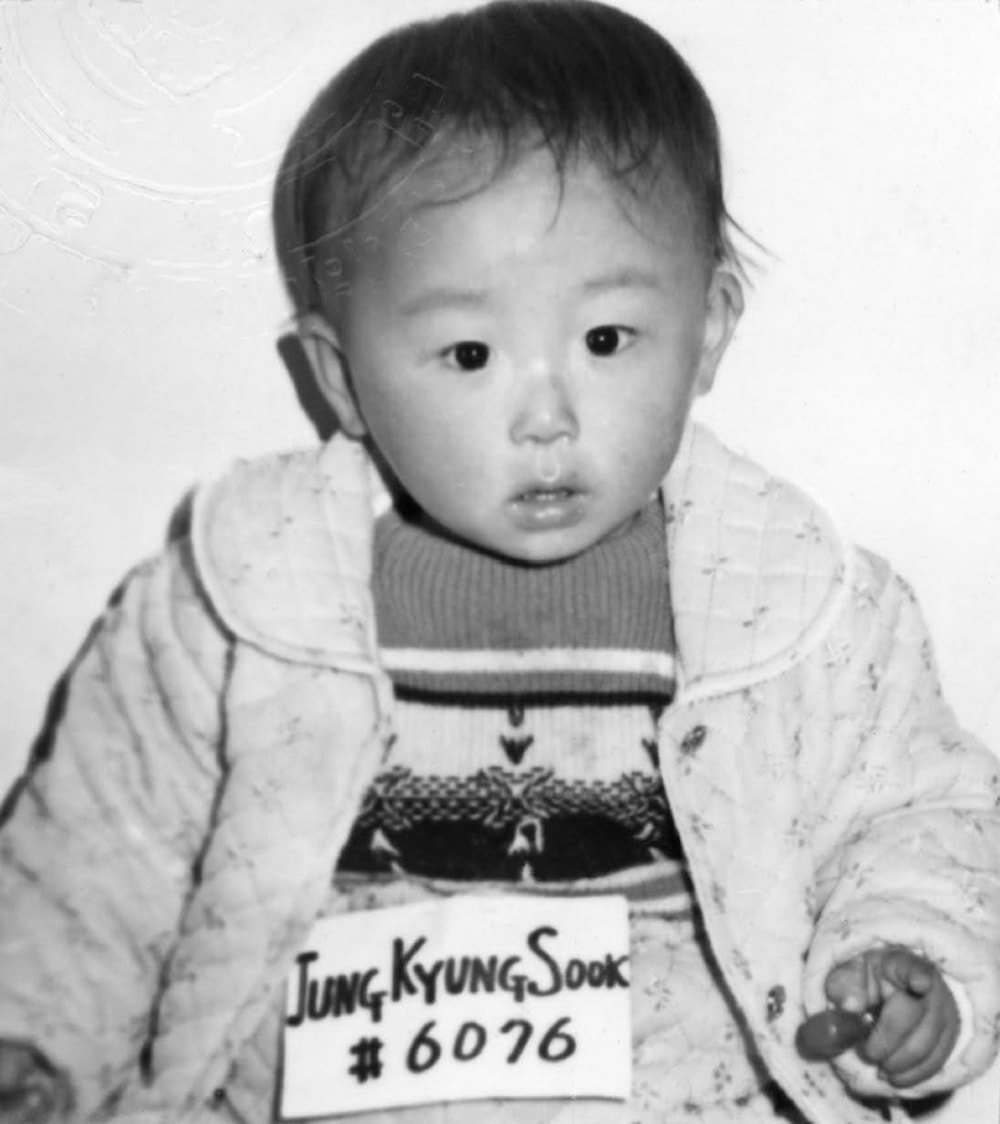

Jung Kyung Sook was only five-moths-old when she was illegally given for adoption to a family in Norway.

Fear gripped her, not of pain, but of her mother’s wrath. She was right. Her mother scolded her, patched the wound, and then devised a humiliating punishment: forcing little Sook to walk beside the family car while she drove slowly, shouting at her through the window all the way to school.

For Sook, now 50, the humiliation of that day pales compared with what she later discovered, that her adoption to Norway had been illegal. Born in 1969, she was sent abroad in 1970 after her mother’s death, without her father’s knowledge.

-

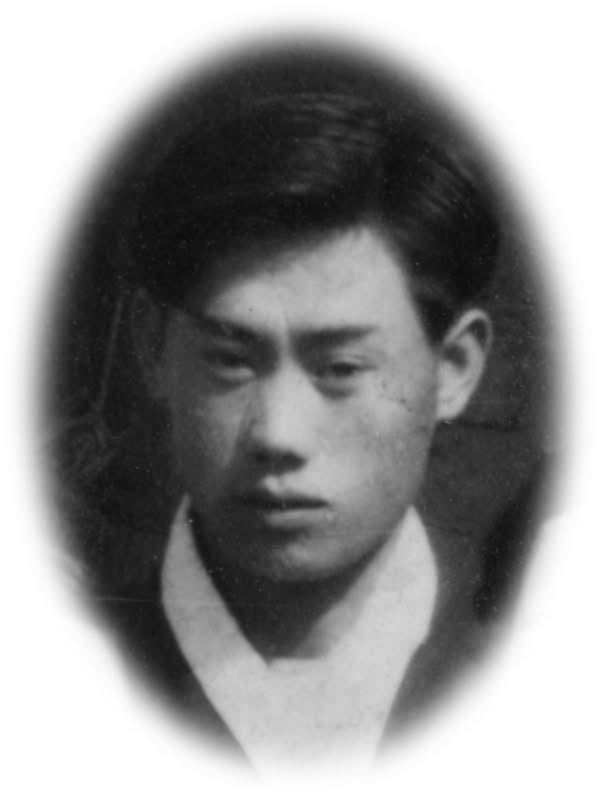

Jung Kyung Sook’s father desperately searched for his little girl for years after she was kidnapped.

In Norway, she endured what she describes as “severe neglect and abuse” in a household plagued by addiction. Only years later did she learn that her father had searched desperately for her for half a decade before dying. Meeting her sisters and extended family in Korea at 18 was a turning point.

“It moved me very much and it has moved me ever since,” she said. “Until then, I had been made to believe I had no family.”

Today, she is petitioning Norwegian authorities to have her adoption declared illegal, seeking compensation, an apology, and the restoration of her South Korean citizenship.

Discovering falsified files

For Uma Feed, the truth arrived in the form of a phone call in Oslo. Adopted in 1983 at just five months old, she had always been told the same story by her adoptive parents and Norwegian authorities: she had been abandoned.

But when her biological parents were traced decades later, she learned the truth: her grandmother had given her away without consent while her mother was hospitalised with tuberculosis. Her devastated parents and brother searched the streets for years, clinging to false records that claimed she had been relocated within Seoul before disappearing abroad.

“My file wasn’t right. It was falsified,” she said. “I wasn’t abandoned. My mother didn’t give me up willingly. I was abducted by my grandmother and sold.”

Feed has since become one of the most prominent voices in the fight against illegal adoption, winning Norway’s prestigious Zola Prize for her activism.

-

Uma Feed at the prestigious Norwegian Zola ceremony, where she received a prize for her long-standing fight against illegal foreign adoption.

A system of deception

Stories like Sook’s and Feed’s are not isolated tragedies. South Korea’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission has found evidence that hospitals, welfare centres, and adoption agencies systematically conspired to strip mothers of their babies from the 1960s through the 1980s.

At least 200,000 children, most born to unmarried and impoverished mothers, were sent abroad during this period, primarily to Scandinavia, the United States, and Australia. Records were falsified, families misled, and in some cases, parents were told their babies had died shortly after birth.

Human rights lawyer Marius Reikeras argues the industry was driven by both social stigma and state strategy. “South Korea’s regimes saw adoption as a tool for economic growth,” he said. “Norway and other Western governments knew illegal adoptions were happening but stayed quiet. In my opinion, this is human trafficking.”

Political reckoning

The revelations are forcing governments to confront their complicity. Norway, long a major recipient of Korean adoptees, has faced repeated convictions in the European Court of Human Rights for violating basic rights in domestic adoption cases. Now it stands accused of enabling international trafficking.

“So we’re talking about, in my opinion, one of the worst human rights scandals in Europe,” Reikeras said. “Governments and adoption agencies allowed this deliberately.”

In 2023, Norway launched a formal inquiry into overseas adoptions after local media uncovered falsified birth certificates and cases of children being “sold.” While Norway has tightened adoption rules, it has resisted calls for a full moratorium. It has suspended adoptions from countries including Thailand, Taiwan, Madagascar, and South Africa, but continues with limited agreements in South Korea, Colombia, and Bulgaria.

Politicians such as Silje Hjemdal have demanded stronger accountability. “There are people who have been wronged, and some may even have been victims of trafficking,” she said. “We must identify them, compensate them, and learn from these mistakes.”

Other Nordic countries are also reassessing their roles. Denmark’s sole adoption agency announced it would phase out international adoptions after evidence of falsified documents. Sweden’s only adoption agency suspended adoptions from South Korea after allegations of forged records emerged.

A global scandal

What began as quiet, individual stories of loss is now being recognised as a global crime. For many adoptees, the discovery has been both liberating and shattering: they were not abandoned, but betrayed—by governments, by agencies, and by the system that sold them as children.

“This was not charity,” said Reikeras. “This was trafficking, sanctioned in plain sight.”

Leila Nezirevic

Leila Nezirevic

5 Min Read

5 Min Read